The State Of LLMs 2025: Progress, Problems, and Predictions

As 2025 comes to a close, I want to look back at some of the year’s most important developments in large language models, reflect on the limitations and open problems that remain, and share a few thoughts on what might come next.

As I tend to say every year, 2025 was a very eventful year for LLMs and AI, and this year, there was no sign of progress saturating or slowing down.

1. The Year of Reasoning, RLVR, and GRPO

There are many interesting topics I want to cover, but let’s start chronologically in January 2025.

Scaling still worked, but it didn’t really change how LLMs behaved or felt in practice (the only exception to that was OpenAI’s freshly released o1, which added reasoning traces). So, when DeepSeek released their R1 paper in January 2025, which showed that reasoning-like behavior can be developed with reinforcement learning, it was a really big deal. (Reasoning, in the context of LLMs, means that the model explains its answer, and this explanation itself often leads to improved answer accuracy.)

1.1 The DeepSeek Moment

DeepSeek R1 got a lot of attention for various reasons:

First, DeepSeek R1 was released as an open-weight model that performed really well and was comparable to the best proprietary models (ChatGPT, Gemini, etc.) at the time.

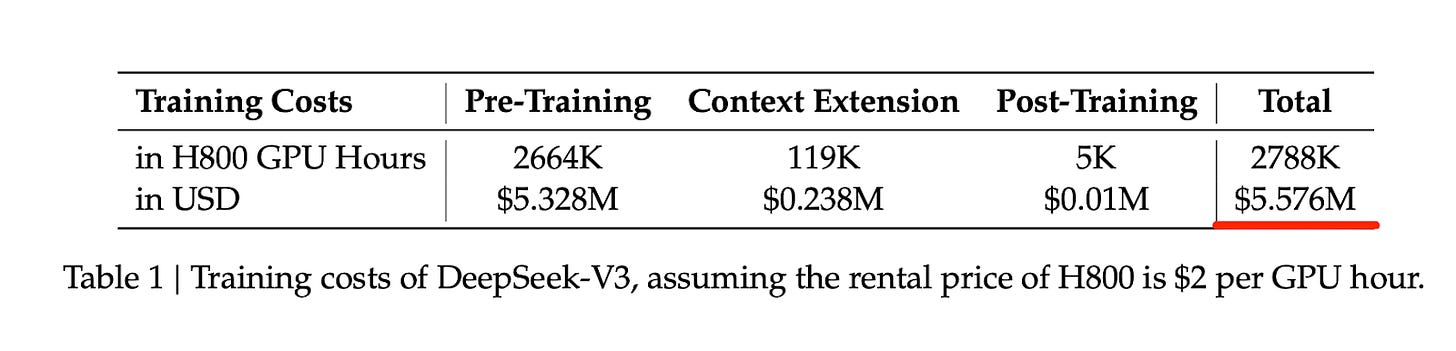

Second, the DeepSeek R1 paper prompted many people, especially investors and journalists, to revisit the earlier DeepSeek V3 paper from December 2024. This then led to a revised conclusion that while training state-of-the-art models is still expensive, it may be an order of magnitude cheaper than previously assumed, with estimates closer to 5 million dollars rather than 50 or 500 million.

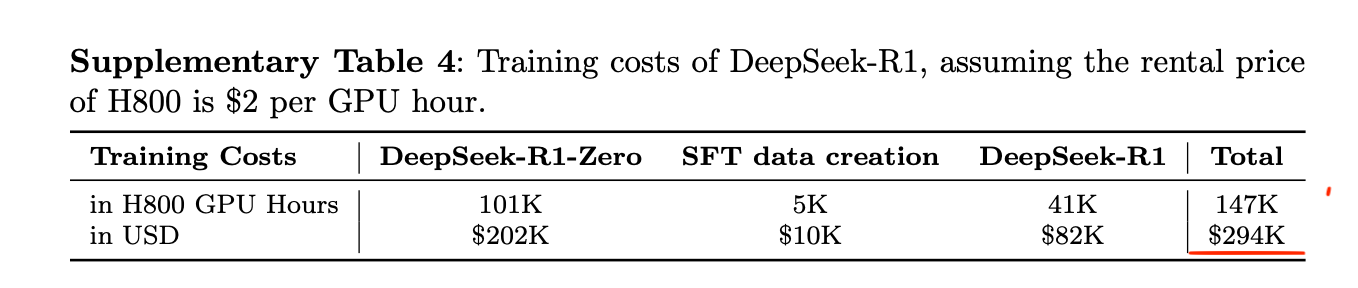

The DeepSeek R1 supplementary materials estimate that training the DeepSeek R1 model on top of DeepSeek V3 costs another $294,000, which is again much lower than everyone believed.

Of course, there are many caveats to the 5-million-dollar estimate. For instance, it captures only the compute credit cost for the final model run, but it doesn’t factor in the researchers’ salaries and other development costs associated with hyperparameter tuning and experimentation.

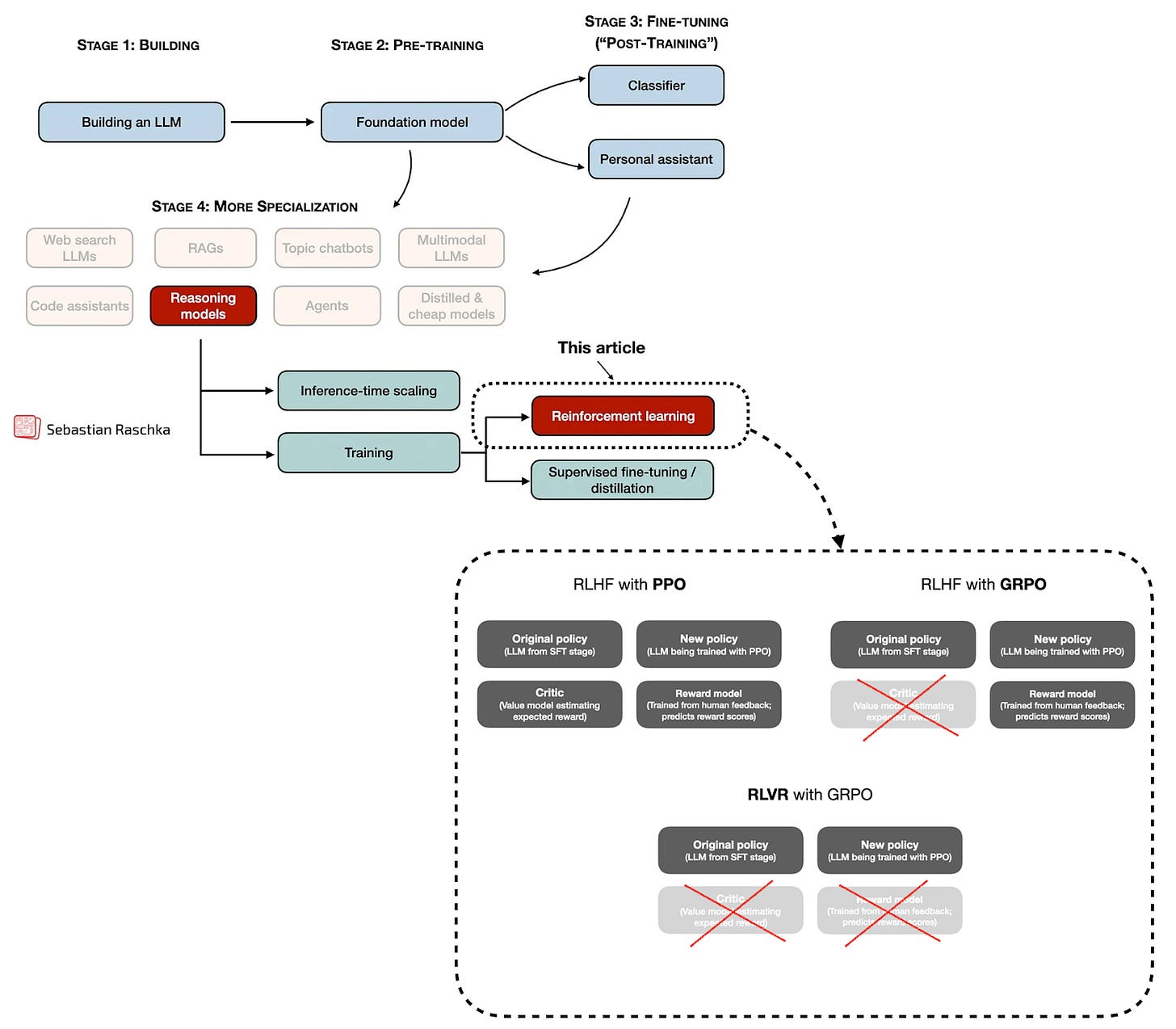

Third, and most interestingly, the paper presented Reinforcement Learning with Verifiable Rewards (RLVR) with the GRPO algorithm as a new (or at least modified) algorithmic approach for developing so-called reasoning models and improving LLMs during post-training.

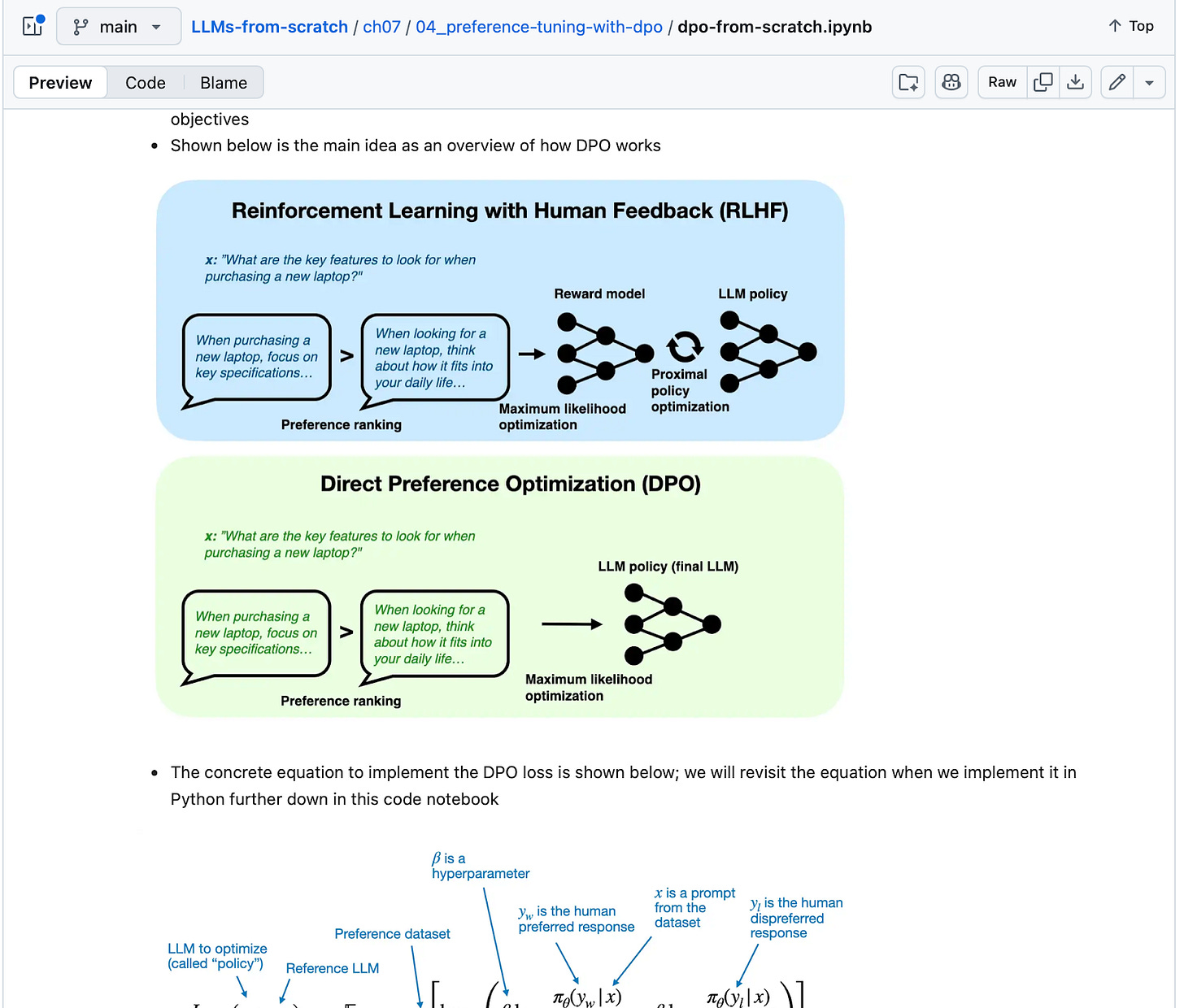

Up to this point, post-training methods like supervised instruction fine-tuning (SFT) and reinforcement learning with human feedback (RLHF), which still remain an important part of the training pipeline, are bottlenecked by requiring expensive written responses or preference labels. (Sure, one can also generate them synthetically with other LLMs, but that’s a bit of a chicken-egg problem.)

What’s so important about DeepSeek R1 and RLVR is that they allow us to post-train LLMs on large amounts of data, which makes them a great candidate for improving and unlocking capabilities through scaling compute during post-training (given an available compute budget).

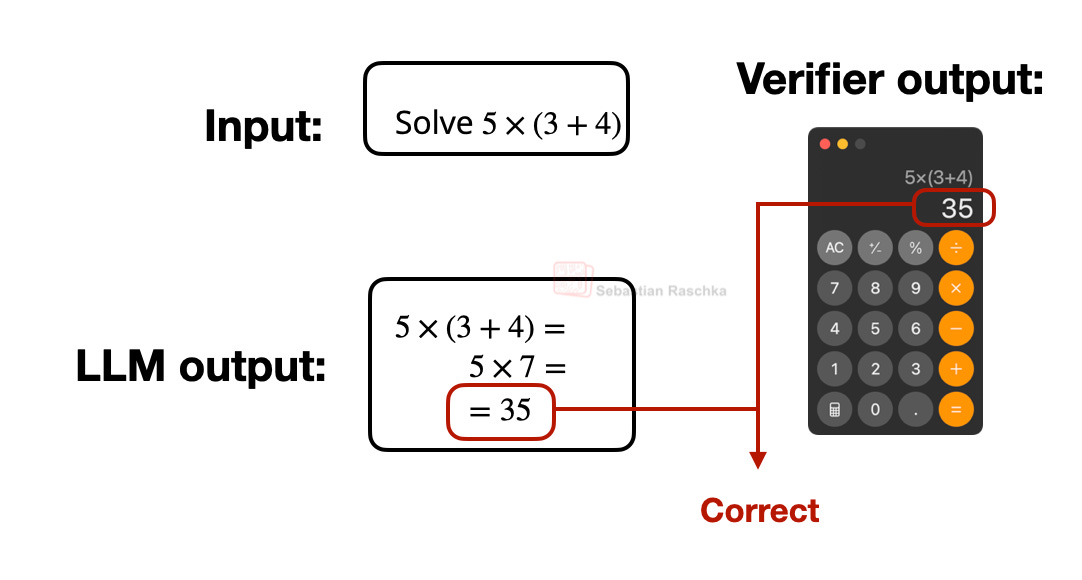

The V in RLVR stands for “verifiable,” which means we can use deterministic approaches to assign correctness labels, and these labels are sufficient for the LLM to learn complex problem-solving. (The typical categories are math and code, but it is also possible to expand this idea to other domains.)

I don’t want to get too lost in technical details here, as I want to cover other aspects in this yearly review article. And whole articles or books can be written about reasoning LLMs and RLVR. For instance, if you are interested to learn more, check out my previous articles:

All that being said, the takeaway is that LLM development this year was essentially dominated by reasoning models using RLVR and GRPO.

Essentially, every major open-weight or proprietary LLM developer has released a reasoning (often called “thinking”) variant of their model following DeepSeek R1.

1.2 LLM Focus Points

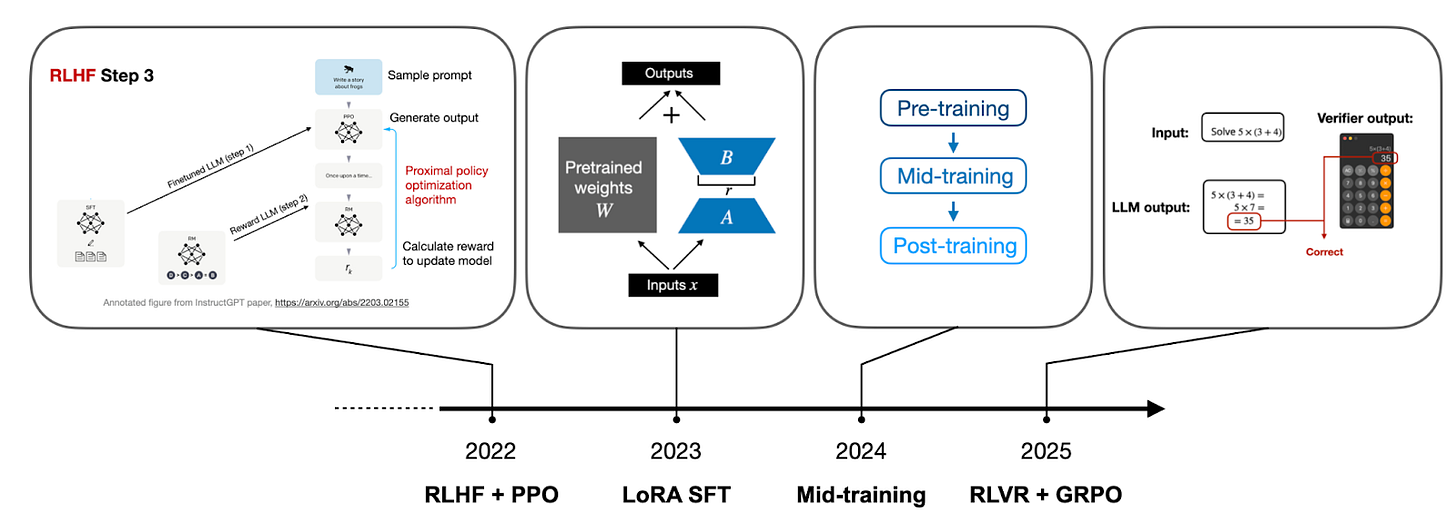

If I were to summarize the LLM development focus points succinctly for each year, beyond just scaling the architecture and pre-training compute, my list would look like this:

2022 RLHF + PPO

2023 LoRA SFT

2024 Mid-Training

2025 RLVR + GRPO

Pre-training is still the required foundation for everything. Besides that, RLHF (via the PPO algorithm) was, of course, what brought us the original ChatGPT model in the first place back in 2022.

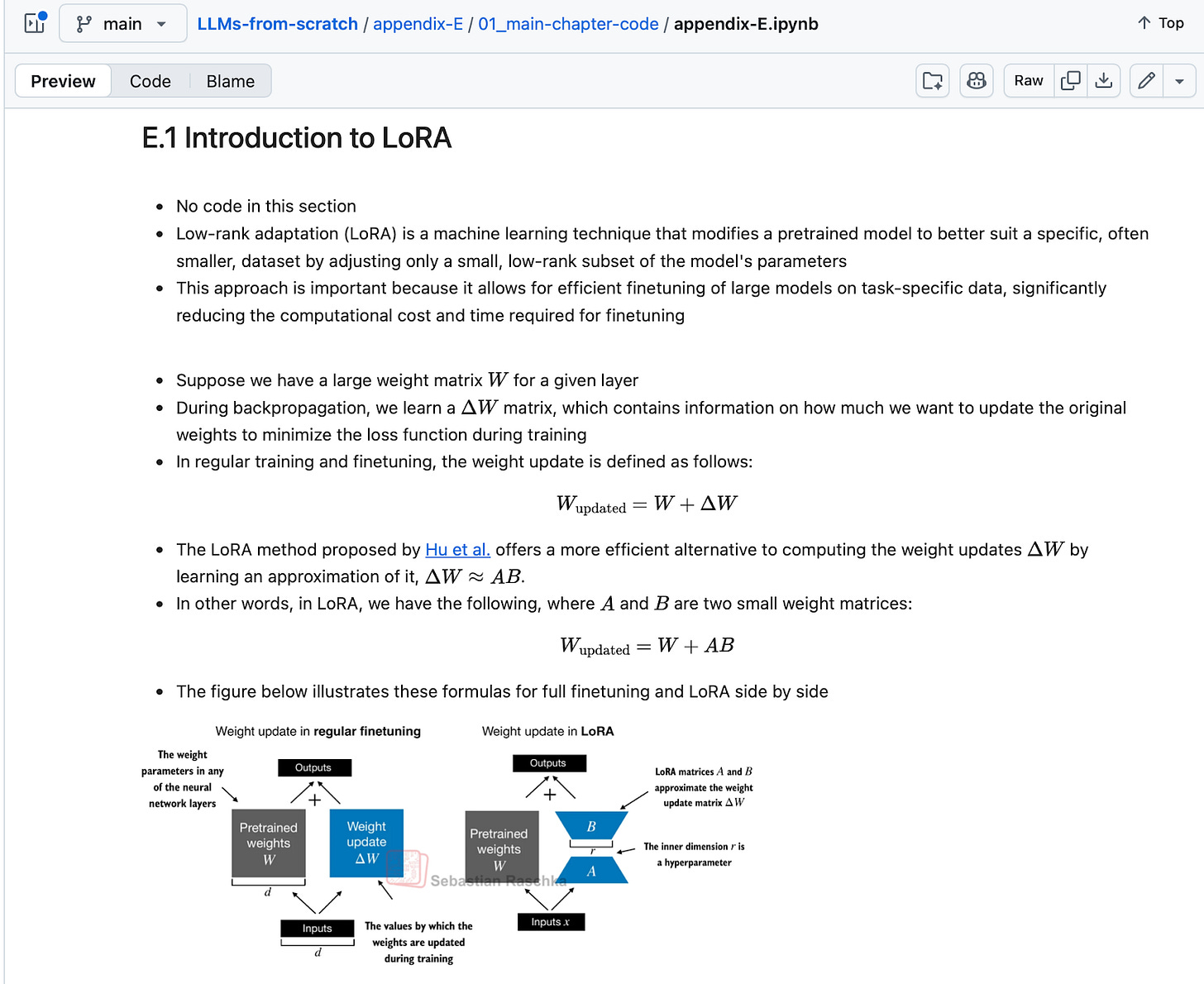

In 2023, there was a lot of focus on LoRA and LoRA-like parameter-efficient fine-tuning techniques to train small custom LLMs.

Then, in 2024, all major labs began making their (pre-)training pipelines more sophisticated by focusing on synthetic data, optimizing data mixes, using domain-specific data, and adding dedicated long-context training stages. I summarized these different approaches in my 2024 article back then (I grouped the techniques under pre-training, because the term “mid-training” hadn’t been coined yet back then):

Back then, I considered these as pre-training techniques, since they use the same pre-training algorithm and objective. Today, these slightly more specialized pre-training stages, which follow the regular pre-training on general data, are often called “mid-training” (as a bridge between regular pre-training and post-training, which includes SFT, RLHF, and now RLVR).

So, you may wonder what’s next?

I think we will see (even) more focus on RLVR next year. Right now, RLVR is primarily applied to math and code domains.

The next logical step is to not only use the final answer’s correctness as a reward signal but also judge the LLM’s explanations during RLVR training. This has been done before, for many years in the past, under the research label “process reward models” (PRMs). However, it hasn’t been super successful yet. E.g., to quote from the DeepSeek R1 paper:

4.2. Unsuccessful Attempts

[...] In conclusion, while PRM demonstrates a good ability to rerank the top-N responses generated by the model or assist in guided search (Snell et al., 2024), its advantages are limited compared to the additional computational overhead it introduces during the large-scale reinforcement learning process in our experiments.

However, looking at the recent DeepSeekMath-V2 paper, which came out last month and I discussed in my previous article From DeepSeek V3 to V3.2: Architecture, Sparse Attention, and RL Updates, I think we will see more of “explanation-scoring” as a training signal in the future.

The way the explanations are currently being scored involves a second LLM. This leads to the other direction I am seeing for RLVR: an extension into other domains beyond math and code.

So, if you asked me today what I see on the horizon for 2026 and 2027, I’d say the following:

2026 RLVR extensions and more inference-time scaling

2027 Continual learning

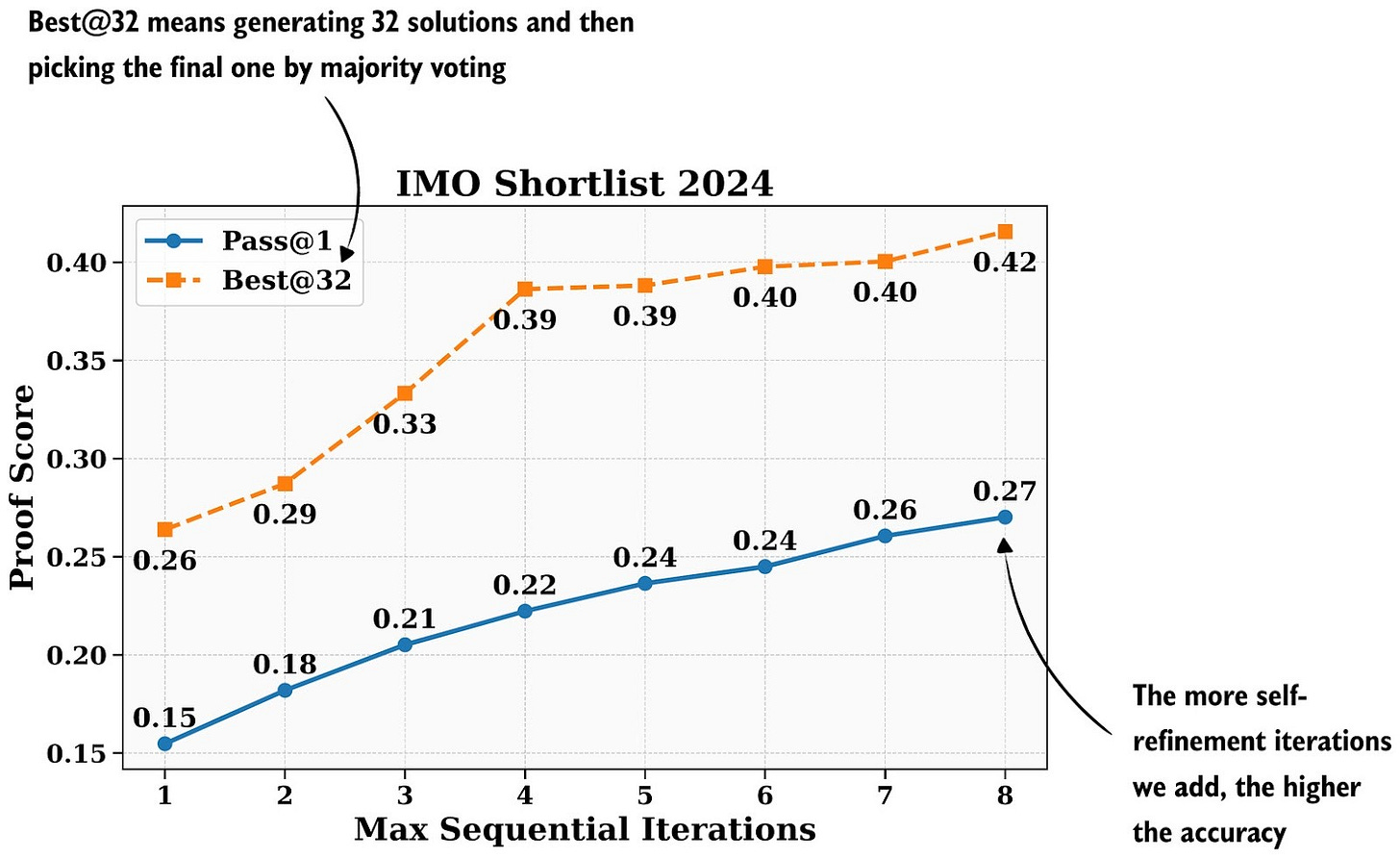

Besides the aforementioned RLVR extensions, I think there will be more focus on inference-time scaling in 2026. Inference-time scaling means we spend more time and money after training when we let the LLM generate the answer, but it goes a long way.

Inference scaling is not a new paradigm, and LLM platforms already use certain techniques under the hood. It’s a trade-off between latency, cost, and response accuracy. However, in certain applications, where accuracy matters more than latency and cost, extreme inference-scaling can totally be worth it. For instance, as the recent DeepSeekV2-Math paper showed, it pushed the model to gold-level performance on a challenge math competition benchmark.

There’s also been a lot of talk among colleagues about continuous learning this year. In short, continual learning is about training a model on new data or knowledge without retraining it from scratch.

It’s not a new idea, and I wonder why it came up so much this year, since there hasn’t been any new or substantial breakthrough in continual learning at this point. The challenge to continual learning is catastrophic forgetting (as experiments with continued pre-training show, learning new knowledge means that the LLM is forgetting old knowledge to some extent).

Still, since this seems like such a hot topic, I do expect more progress towards minimizing catastrophic forgetting and making continual learning method development an important development in the upcoming years.

2. GRPO, the Research Darling of the Year

Academic research in the era of expensive LLMs has been a bit challenging in recent years. Of course, important discoveries that became mainstream and key pillars of LLM progress and breakthroughs can be made in academia despite (or because of) smaller budgets.

In recent years, popular examples include LoRA (LoRA: Low-Rank Adaptation of Large Language Models 2021) and related methods for parameter-efficient fine-tuning.

Another one is DPO (Direct Preference Optimization: Your Language Model is Secretly a Reward Model) and related methods for reward-model-free alignment as an alternative reinforcement learning with human feedback.

In my bubble, this year’s research highlight has been GRPO. Although it was introduced in the DeepSeek R1 paper rather than originating from academia, it has still made for an exciting year for researchers: both RLVR and GRPO are conceptually interesting and, depending on scale, not prohibitively expensive to experiment with.

So, there have been many mathematical improvements to GRPO that I saw in the LLM research literature this year (from both companies and academic researchers), which were later adopted in the training pipelines of state-of-the-art LLMs. For instance, some of the improvements include the following:

Zero gradient signal filtering (DAPO by Yu et al., 2025)

Active sampling (DAPO by Yu et al., 2025)

Token-level loss (DAPO by Yu et al., 2025)

No KL loss (DAPO by Yu et al., 2025 and Dr. GRPO by Liu et al., 2025)

Clip higher (DAPO by Yu et al., 2025)

Truncated importance sampling (Yao et al., 2025)

No standard deviation normalization (Dr. GRPO by Liu et al., 2025)

KL tuning with domain‑specific KL strengths (zero for math)

Reweighted KL

Off‑policy sequence masking

Keep sampling mask for top‑p / top‑k

Keep original GRPO advantage normalization

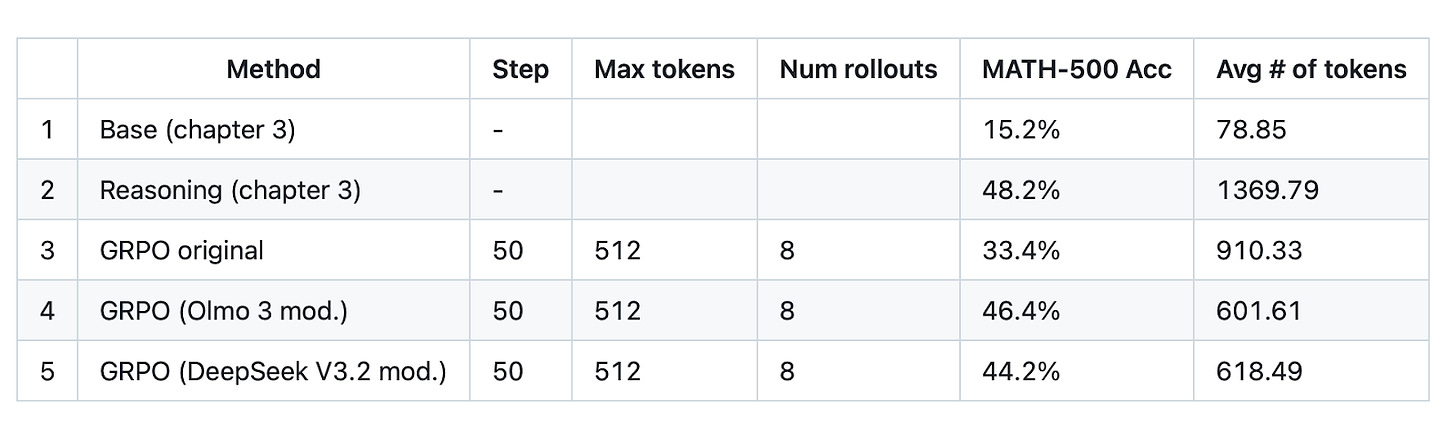

I can confirm that these GRPO tricks or modifications have a huge impact in practice. For instance, with some or multiple of these modifications in place, bad updates no longer corrupt my training runs, and I no longer need to reload checkpoints periodically.

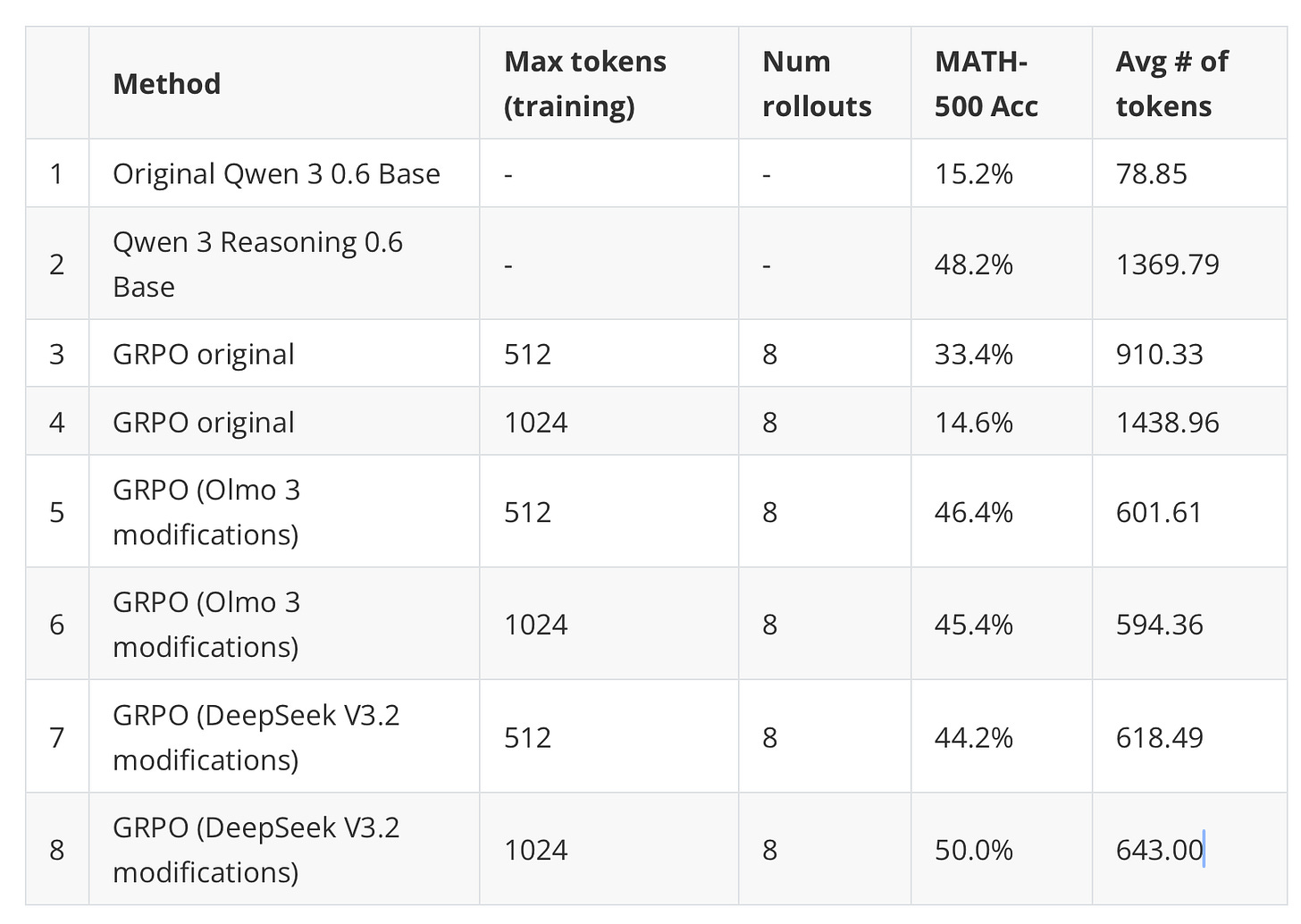

And even for very short runs, I observed a big gain when adopting these tricks:

Anyways, I have a vanilla GRPO script in my Build A Reasoning Model (From Scratch) repository if you want to toy around with it. (I will add more ablation studies with the respective modifications soon.)

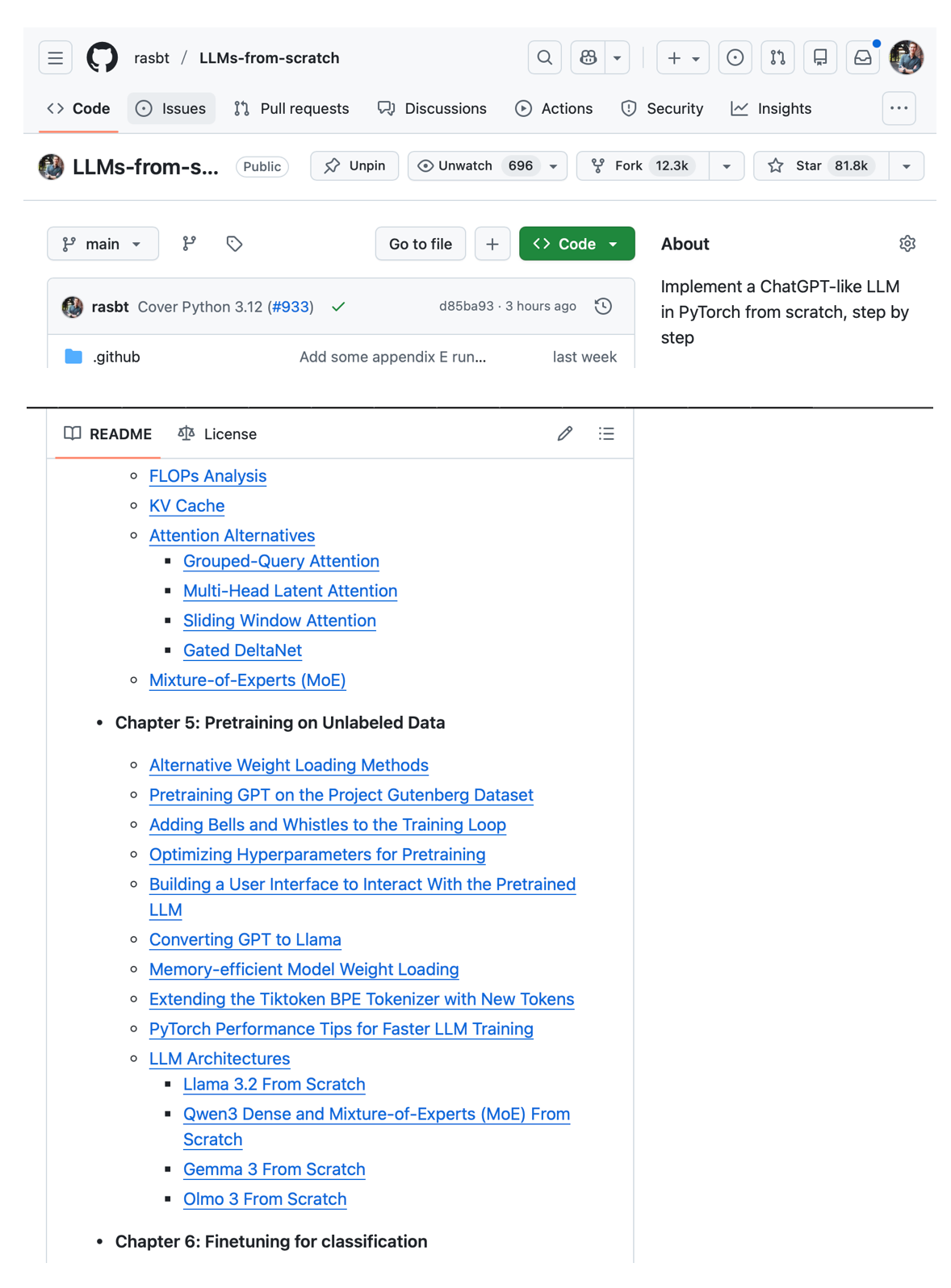

3. LLM Architectures: A Fork in the Road?

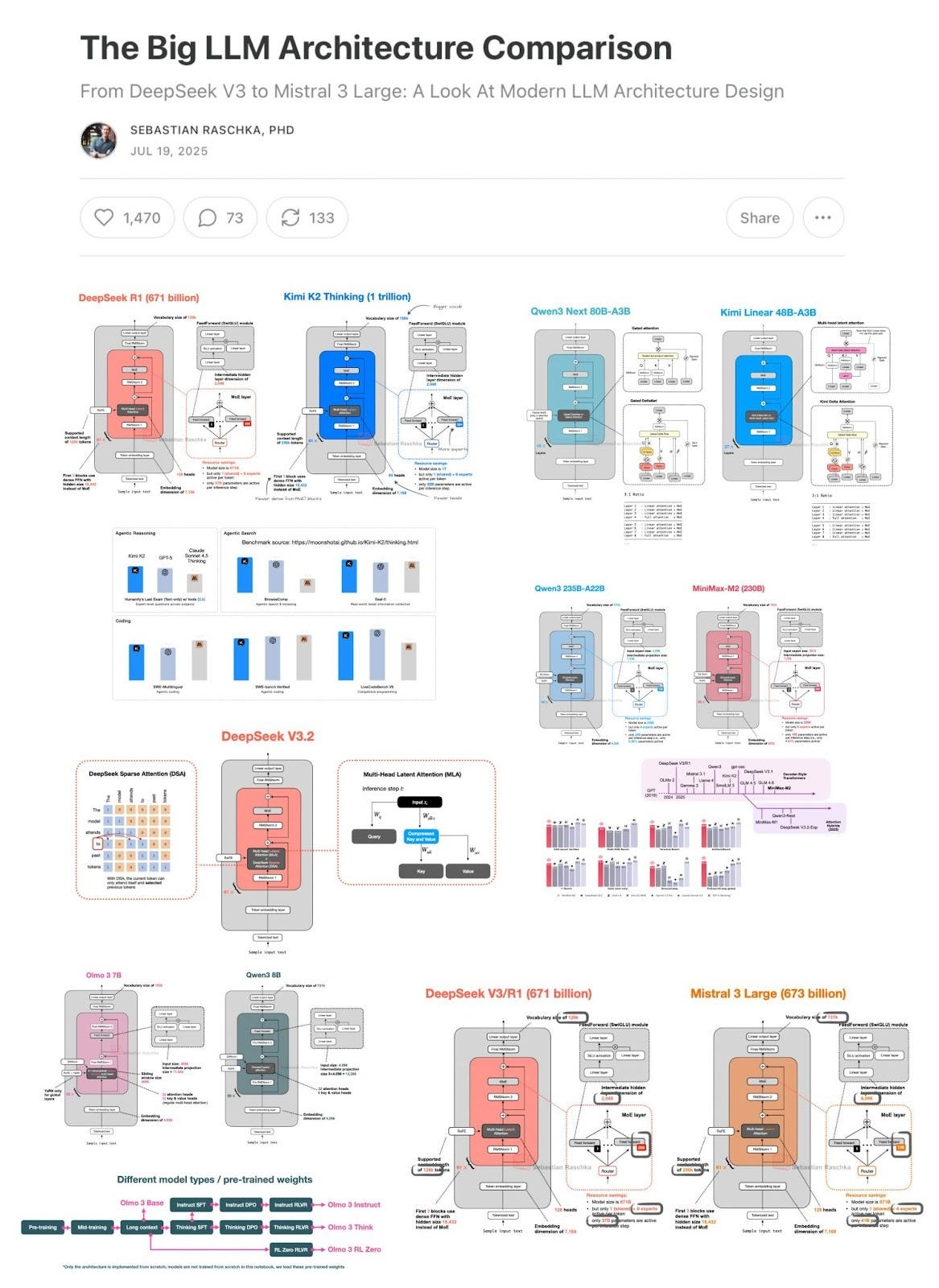

When it comes to LLM architectures, state-of-the-art models still use the good old decoder-style transformer. However, this year, open-weight LLMs more or less converged on using mixture-of-experts (MoE) layers, as well as at least one “efficiency-tweaked” attention mechanism: Grouped-query attention, sliding-window attention, or multi-head latent attention.

Beyond those fairly standard LLM architectures, we have also seen more drastic efficiency tweaks targeting the attention mechanism to scale linearly with sequence length. Examples of this include the Gated DeltaNets in Qwen3-Next and Kimi Linear, as well as the Mamba-2 layers in NVIDIA’s Nemotron 3.

Anyways, I don’t want to go into too much detail here because I have a whole 13k-word and recently-updated article dedicated to these architectures here if you want to learn more: The Big LLM Architecture Comparison.

My prediction is that we will keep building, and with the transformer architecture for at least a couple more years, at least when it comes to state-of-the-art modeling performance.

At the same time, I do think that we will see more and more of these efficiency and engineering tweaks like Gated DeltaNet and Mamba layers because at the scale at which LLMs are trained, deployed, and used, it just makes sense from a financial perspective for these companies, which are still burning a lot of money on serving LLMs.

This doesn’t mean that there are no other alternatives out there. As I’ve written about in Beyond Standard LLMs, for instance, text diffusion models are an interesting approach. Right now, they fall into the category of experimental research models, but Google shared that they will release a Gemini Diffusion model. It won’t rival their state-of-the-art offerings in modeling quality, but it will be really fast and attractive for tasks with low-latency requirements (e.g., code completion).

Also, two weeks ago, the open-weight LLaDA 2.0 models dropped. The largest one, at 100B parameters, is the largest text diffusion model to date and is on par with Qwen3 30B. (Yes, it doesn’t push the state-of-the-art overall, but it’s still a notable release in the diffusion model space.)

4. It’s Also The Year of Inference-Scaling and Tool Use

Improving LLMs by scaling training data and architectures is an established formula that (still) keeps on giving. However, especially this year, it’s no longer the “only” sufficient recipe.

We saw this with GPT 4.5 (Feb 2025), which was rumored to be much larger than GPT 4 (and the later-released GPT 5), and pure scaling alone is not generally the most sensible way forward. The capabilities of GPT 4.5 may have been better than those of GPT 4, but the increased training budget was considered a “bad bang for the buck.”

Instead, better training pipelines (with greater focus on mid- and post-training) and inference scaling have driven much of the progress this year.

For example, as discussed earlier, when talking about DeepSeekMath-V2, which achieved gold-level math performance, inference scaling is one of the levers we can pull to get LLMs to solve extremely complex tasks on demand (GPT Heavy Thinking or Pro are other examples; it doesn’t make sense to use these for everything due to the high latency and cost, but there are certain examples, like challenging math or coding problems, where the intense inference-scaling makes sense.)

Another major improvement came from training LLMs with tool use in mind. As you may know, hallucinations are one of the biggest problems of LLMs. Arguably, hallucination rates keep improving, and I think this is largely due to said tool use. For instance, when asked who won the FIFA soccer World Cup in 1998, instead of trying to memorize, an LLM can use a traditional search engine via tool use and select and scrape this information from a credible website on this topic (for example, in this case, the official FIFA website itself). The same goes for math problems, using calculator APIs, and so forth.

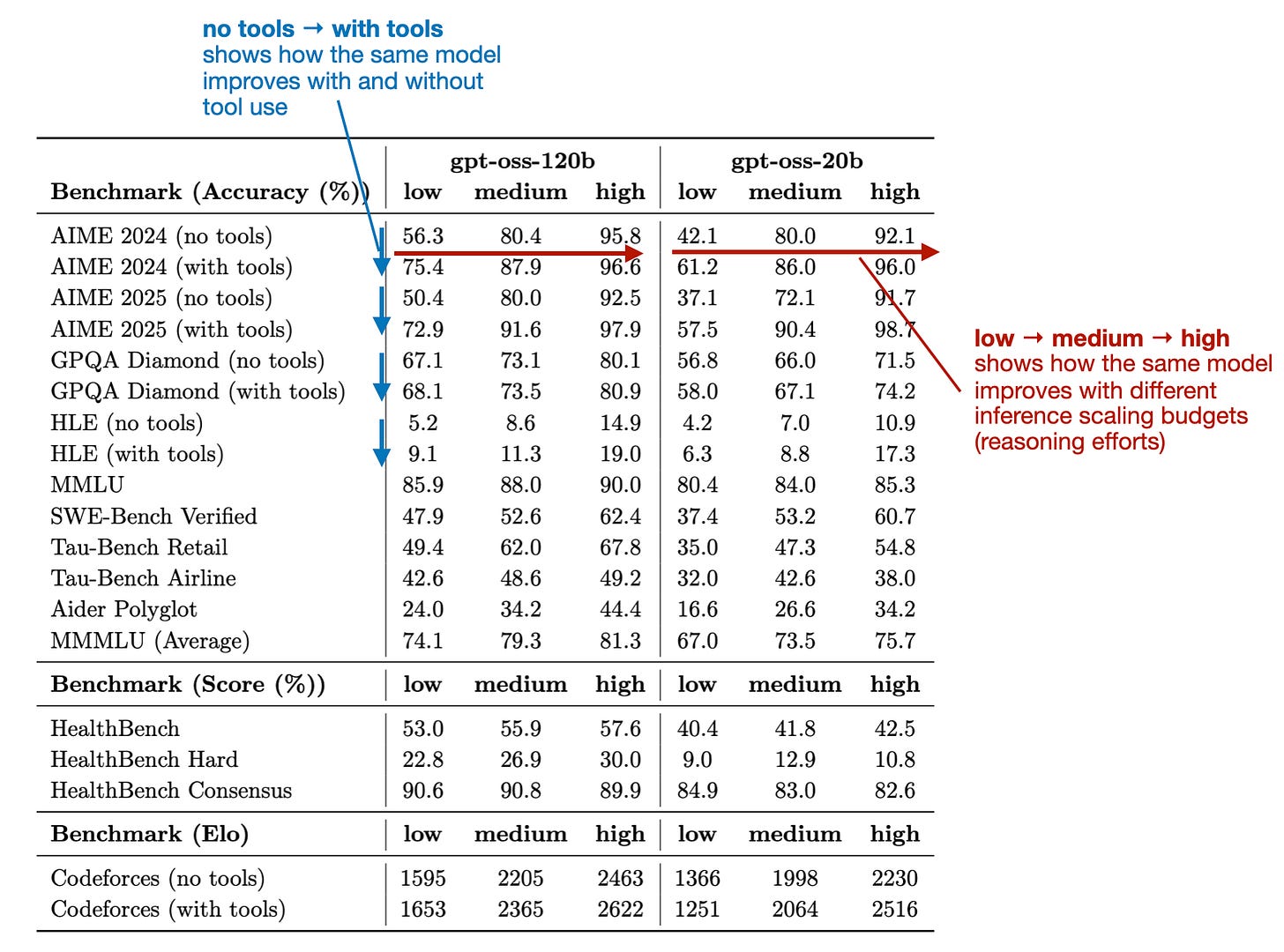

For instance, OpenAI’s gpt-oss models were among the earlier open-weight models released this year that were specifically developed with tool use in mind.

Unfortunately, the open-source ecosystem hasn’t fully caught up with that yet, and many, if not most, tools still default to running these LLMs in non-tool-use mode. One reason is that this is a newer, evolving paradigm, for which the tooling needs to be adapted. The other reason is also that this is a harder problem, to solve due to security (giving an LLM unrestricted tool use access could potentially be a security risk or wreak other kinds of havoc on your system. I think the sensible question to always ask is: would you trust a new intern to do this with this amount of access to your system?)

I do think that, in the coming years, enabling and allowing tool use will become increasingly common when using LLMs locally.

5. Word of the Year: Benchmaxxing

If I had to pick a word or trend that describes LLM development this year, it would be “benchmaxxing”.

Here, benchmaxxing means there’s a strong focus on pushing leaderboard numbers, sometimes to the point where benchmark performance becomes a goal in itself rather than a proxy for general capability.

A prominent example was Llama 4, which scored extremely well across many established benchmarks. However, once users and developers got their hands on it, they realized that these scores didn’t reflect the real-world capabilities and usefulness.

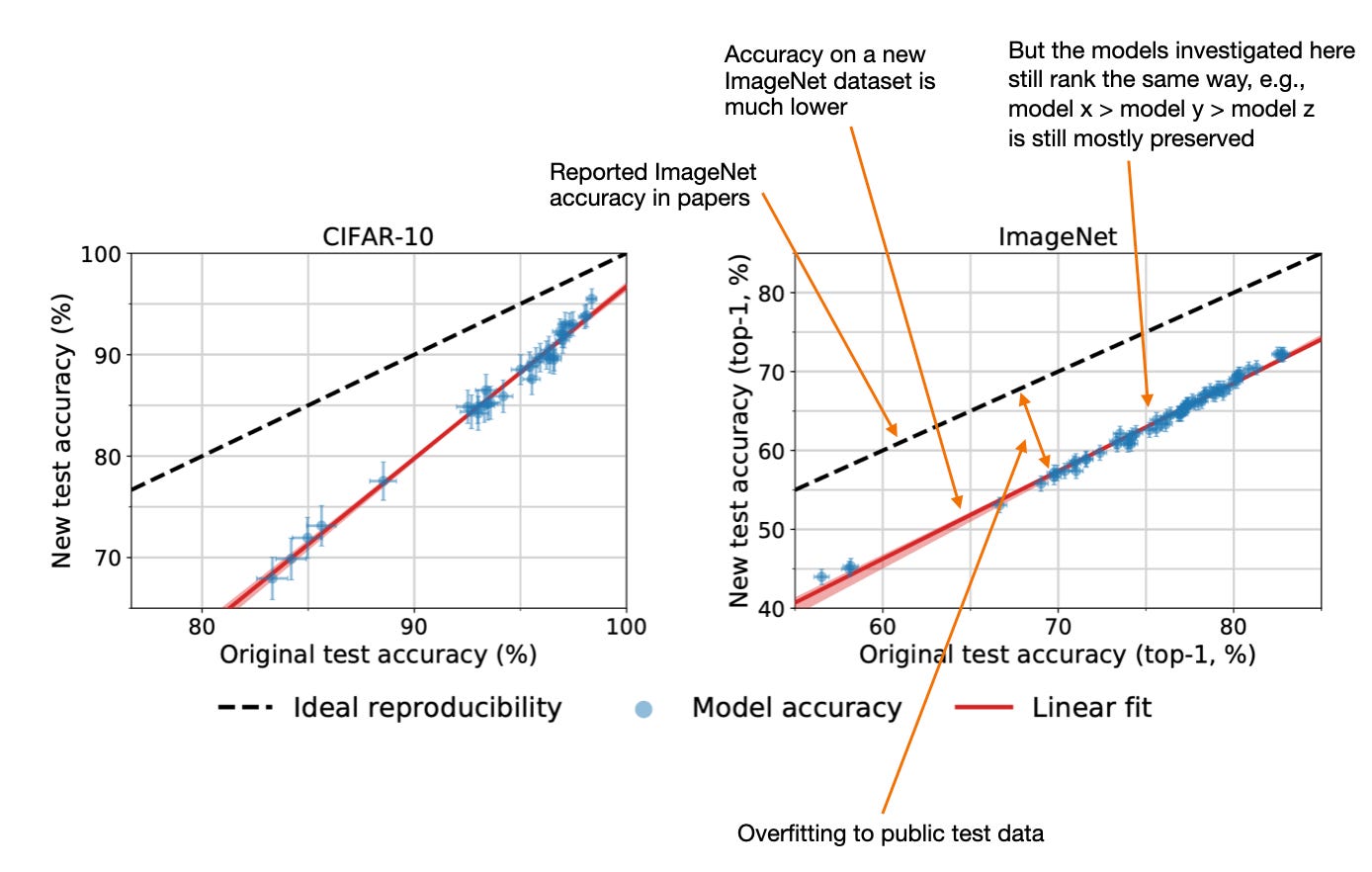

As the popular saying goes, if the test set is public, it isn’t a real test set. And the problem these days is that test set data is not only part of the training corpus (intentionally or unintentionally), but is also often directly optimized for during LLM development.

Back in the day, even if benchmark scores on public test sets were inflated, at least the model ranking was still preserved. E.g., see the annotated figure from the 2019 Do ImageNet Classifiers Generalize to ImageNet? paper below.

In LLM development, this has reached a point where benchmark numbers are no longer trustworthy indicators of LLM performance.

However, I do think benchmarks remain necessary thresholds that LLMs must cross. I.e., if I see that an LLM scores below X on benchmark Y, I already know it’s not a good LLM. However, if it scores above X on benchmark Y, that doesn’t imply it’s much better than another LLM that scores above X on the same benchmark.

Another aspect to consider is that image classifiers have only one job, namely, classifying images. However, LLMs are used for many different tasks: translating text, summarizing text, writing code, brainstorming, solving math problems, and many more. Evaluating image classifiers, where a clear metric such as classification accuracy is available, is much simpler than evaluating LLMs on both deterministic and free-form tasks.

Besides trying out LLMs in practice and constantly generating new benchmarks, there’s unfortunately no solution to this problem.

By the way, if you are curious to learn more about the main categories of LLM evaluation, you might like my article Understanding the 4 Main Approaches to LLM Evaluation (From Scratch):

6. AI for Coding, Writing, and Research

Since it comes up so often, I wanted to share my two cents about LLM replacing humans for certain types of tasks (or even jobs).

At a high level, I see LLMs as tools that give people in certain professions “superpowers”. What I mean is that when LLMs are used well, they can make individuals substantially more productive and remove a lot of friction from day-to-day work. This ranges from relatively mundane tasks, such as making sure you title-cased section headers consistently, to finding complex bugs in larger code bases.

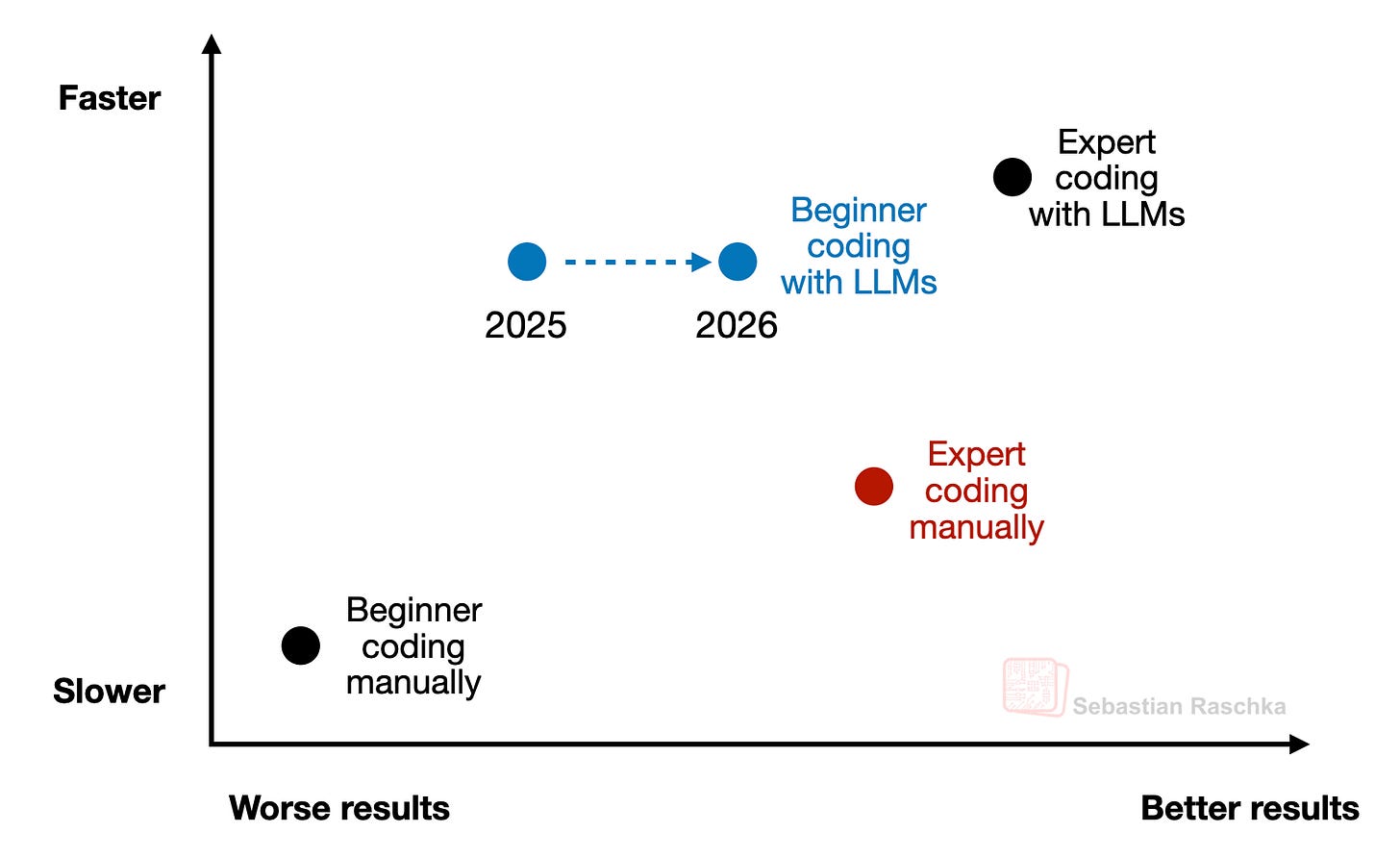

6.1 Coding

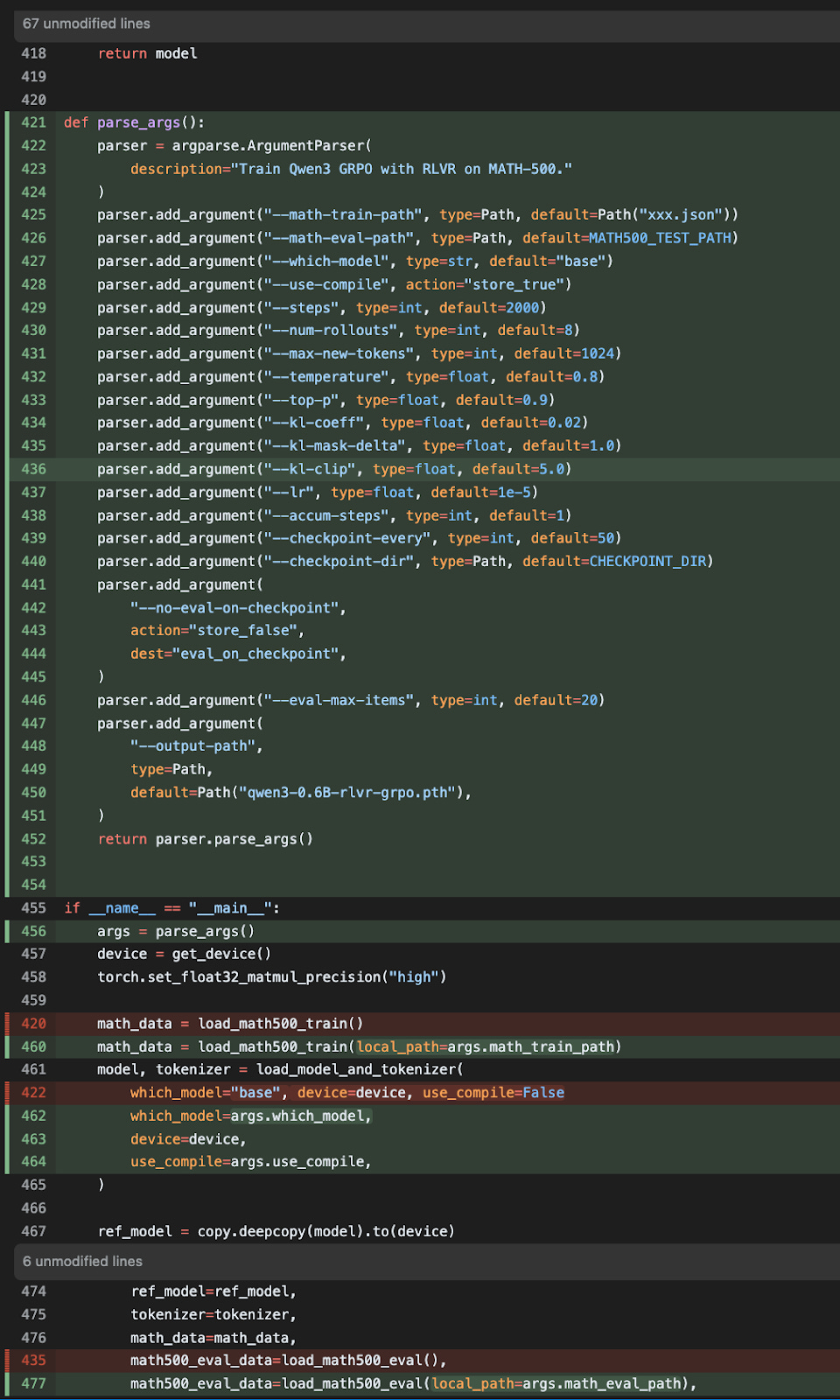

Today, I still write most of the code I care about myself. With “care about,” I mean in contexts where it matters that I understand the code and that the code is correct. For example, if I set up an LLM training script, I would implement and carefully go over the training logic. This is a) to make sure it’s doing what I think it should be doing and b) to preserve my knowledge and expertise in this task. However, I now use LLMs to add the more mundane code around it, such as adding a command-line argparse boilerplate so I can use my own code more conveniently from the command line.

But I also more and more rely on LLMs to spot issues, suggest improvements, or sanity-check ideas. At the same time, I want to understand what I am building, and as a personal goal, I aim to deepen my knowledge and skills and continue growing my expertise.

At the same time, LLMs have been extremely valuable for tasks outside my core expertise. They let me automate things I would otherwise not have had the time or energy to tackle. One example is a recent tool I wrote to extract and back up my Substack articles as Markdown. (I draft everything in Markdown, but I often edit and extend articles directly in the Substack editor, so my local drafts are not always up to date). LLMs also helped me clean up the CSS on my website, which had accumulated years of duplication and inconsistencies. And there are many similar cases where I used LLMs this year.

Or, in short, I think the trick here is to recognize when and when not to use LLMs. And how to use LLMs in a way that helps you grow your expertise in a way that also feels satisfying.

6.2 Codebases and code libraries

LLMs got better at writing code, but despite what I hear some other people say, I don’t think that code is or will become ephemeral or obsolete. LLMs give people superpowers to generate certain coding projects that would have taken them lots of effort to create themselves.

However, pure LLM-generated code bases don’t replace expert-crafted code bases. These expert code bases may have even been created by human coders using LLMs themselves. But the key point is that someone with expertise in this area has invested a lot of time and effort in creating, testing, and refining it. It would take someone else a lot of work to replicate it, so why not adopt it if it exists?

In short, I think that an expert full-stack web developer who has learned about good design patterns and trade-offs and has studied, seen, and built many platforms in their career will be able to build a better platform than a random person prompting an LLM to build one.

The awesome thing is that a random person can now build a platform, even if it’s not the best one. However, using and prompting LLMs will only get that person so far, and the platform’s quality may plateau. So, if the person really cares about improving the platform, it would be a good idea to go deeper here, learn how others build platforms, and come back with more knowledge to use LLMs more effectively to guide and improve the platform design.

6.3 Technical writing and research

Similar to coding, I do not see LLMs making technical writing obsolete. Writing a good technical book takes thousands of hours and deep familiarity with the subject. That process may involve LLMs to improve clarity, check technical correctness, explore alternatives, or run small experiments, but the core work still depends on human judgment and expertise.

Yes, LLMs can make technical books better. They can help authors find errors, expand references, and generally reduce time spent on mundane tasks. This frees up more time for the deep work that actually requires creativity and experience.

From the reader’s perspective, I also do not think LLMs replace technical writing. Using an LLM to learn about a topic works well for quick questions and beginner-level explanations. However, this approach quickly becomes messy when you want to build a deeper understanding.

At that point, instead of potentially wasting hours yourself to try to filter through LLM responses about a topic you are trying to learn about but are not an expert in (yet), it often makes sense to follow a structured learning path designed by an expert. (The expert may or may not have used LLMs.)

Of course, it still makes perfect sense to use LLMs for clarifying questions or exploring side paths while taking a course or learning from a book. It’s also great to have it design quizzes or exercise to practice the knowledge.

Overall, I see LLMs as a net win for both writers and readers.

But I also think the trick here is to learn to recognize when and when not to use LLMs. For instance, the main downside is that it can be tempting to immediately use an LLM when a topic gets hard, because struggling through a problem yourself first often leads to much stronger learning.

I see research in much the same way. LLMs are very useful for finding related literature, spotting issues in mathematical notation, and suggesting follow-up experiments. But it still makes sense to keep a human researcher in the driver’s seat.

Maybe the rules of thumb here are something like this:

If this (research) article or book was entirely generated by a human, it could have potentially been further improved

And if this (research) article or book could have been generated by just prompting an LLM, then it’s probably not novel and/or deep enough.

6.4 LLMs and Burnout

LLMs are still fairly new and evolving, and I think there is also a less discussed downside to overusing LLMs. For instance, I think that if the model does all the doing and the human mainly supervises, work can start to feel hollow.

Sure, some people genuinely enjoy focusing on managing systems and orchestrating workflows, and that is a perfectly valid preference. But for people who enjoy doing the thing itself, I think this mode of work can accelerate burnout. (This is likely especially true for companies that expect more results faster since we now have LLMs.)

There is a special satisfaction in struggling with a hard problem and finally seeing it work. I do not get the same feeling when an LLM one-shots the solution. I guess it’s similar to cooking (this is just something that came to mind, and I’m not a great cook). If you enjoy making pizza, using pre-made dough and only adding toppings likely removes much of the joy, and cooking becomes a means to an end. That’s not necessarily bad, but I think if you are doing this work for many hours every day over a longer stretch (months or years), I can see how it will feel empty and eventually lead to burnout.

So, a selfish perspective is that writing code is also more enjoyable than reading code. And you may agree that creating pull requests is usually more fun than reviewing them (but of course, this is not true for everyone).

Maybe a good, idealized (but not perfect) analogy for how we should use AI in a sustainable way is chess.

Chess engines surpassed human players decades ago, yet professional chess played by humans is still active and thriving. I am not a chess expert, but I’d say the game has probably even become richer and more interesting.

Based on what I heard (e.g., based on Kasparov’s Deep Thinking book and podcasts featuring Magnus Carlsen), modern players have been using AI to explore different ideas, challenge their intuitions, and analyze mistakes with a level of depth that simply was not possible before.

I think this is a useful model for how to think about AI in other forms of intellectual work. Used well, AI can accelerate learning and expand what a single person can reasonably take on. I think we should treat it more as a partner rather than a replacement.

But I also think if AI is used to outsource thinking and coding entirely, it risks undermining motivation and long-term skill development.

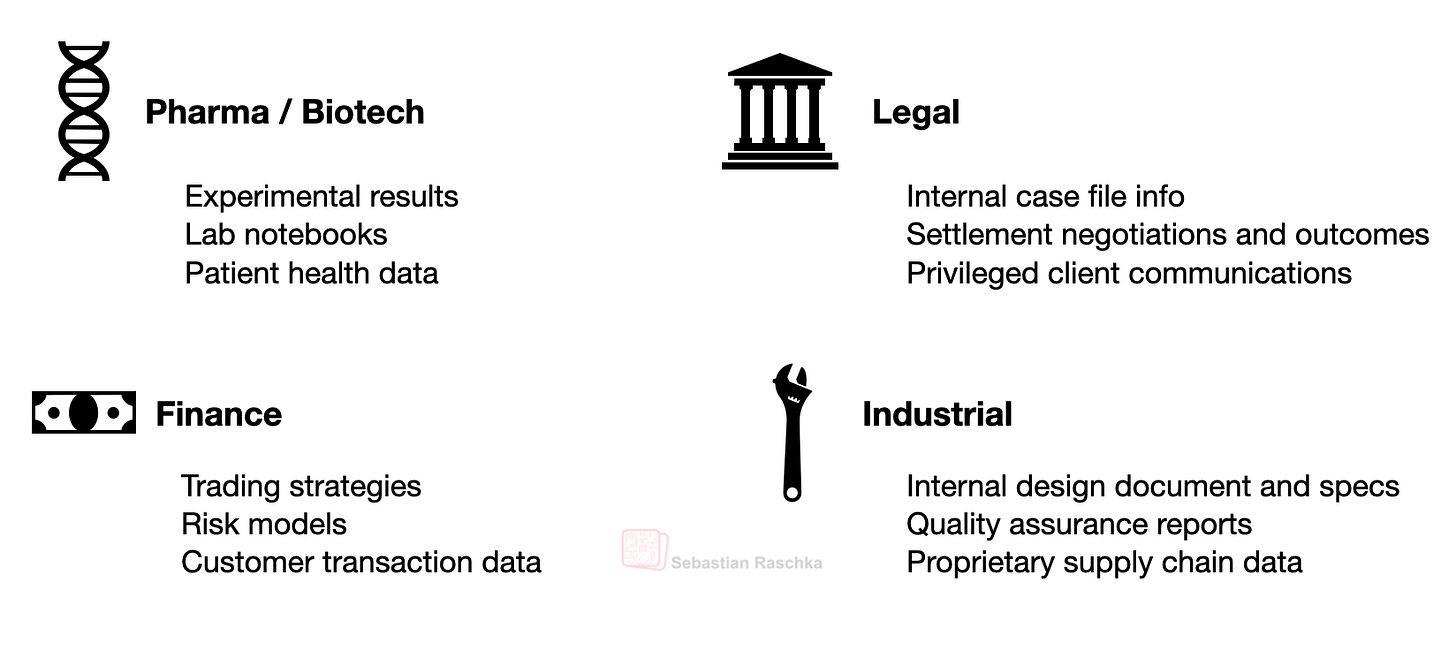

7. The Edge: Private data

The general coding, knowledge-answering, and writing capabilities of LLMs keep improving. This is largely true because scaling still delivers a positive return on investment thanks to improvements in training pipelines and paradigms (e.g., RLVR), as well as in inference scaling and tool use.

However, this will begin to plateau at some point (similar to what we have seen for the GPT 4 to GPT 4.5 development), unless we keep on inventing new training methods and/or architectures (at this point, no one knows what these might look like, yet).

LLMs are currently able to solve a lot of general tasks and low(er) hanging fruit. But to entrench them in certain industries, it would require more domain specialization. I think LLM providers would love to get their hands on high-quality, domain-specific data. For now, it looks like this will be a challenge.

For instance, it appears that most of the companies approached have declined such deals precisely because the data is proprietary and core to their business differentiation. (I’ve heard this from multiple sources, and there was also a The Information article on this topic.)

In my opinion, it makes total sense. I think that selling valuable and proprietary data, which can give a company an edge one day, to OpenAI or Anthropic could be a bit short-sighted.

Right now, LLM development is prohibitively expensive and challenging at scale, which is why only a few major companies develop state-of-the-art LLMs. However, I think LLM development is becoming increasingly commoditized, as LLM developers frequently rotate between employers and will eventually be hired by bigger financial institutions, biotech companies, and others with budgets to develop competitive in-house LLMs that benefit from their private data.

These LLMs don’t even have to be entirely trained from scratch; many state-of-the-art LLMs like DeepSeek V3.2, Kimi K2, and GLM 4.7 are being released and could be adapted and further post-trained.

8. Building LLMs and Reasoning Models From Scratch

You may be wondering what I have been up to this year. My focus has been almost entirely on LLM-related work. Last year, I decided to become independent and start my own company, mainly to have more time to work on my own research, books, Substack writing, and industry collaborations.

As an independent researcher, consulting projects are part of what makes this setup sustainable. This includes the usual everyday expenses (from groceries to health insurance), but also less visible costs such as cloud compute for said experiments.

Over time, my goal is to further reduce consulting work and spend more time on long-form research and writing, especially the technical deep dives I share here.

I am in the fortunate position that many companies have reached out about full-time roles, which would be a viable option if independence does not work out, but for now, I plan to remain independent.

If you find my work useful, and if you can, subscribing to the Substack or picking up one of my books genuinely helps make this kind of work sustainable, and I really appreciate the support.

One of my personal highlights this year has been the positive feedback on my book Build A Large Language Model (From Scratch). I received many thoughtful messages from readers at companies and universities all around the world.

The feedback spans a wide range of use cases, from college professors adopting the book as a primary textbook to teach how LLMs work, to former students who used it to prepare for job interviews and land new roles, to engineers who relied on it as a stepping stone for implementing custom LLMs in production.

I was also excited to learn that the book has now been translated into at least nine languages.

Many readers also asked whether there would be a second edition covering newer and more advanced topics. While that is something I have thought about, I am cautious about making the book less accessible. For example, replacing standard multi-head attention with more complex variants such as multi-head latent attention, as used in some newer DeepSeek models, would raise the barrier to entry quite a bit.

Instead, for now, I prefer to keep the book as is, since it works really well for people who want to get into LLMs. And for readers interested in more advanced material, as a follow-up, I added substantial bonus material to the book’s GitHub repository over the course of the year. I plan to continue expanding these materials over time.

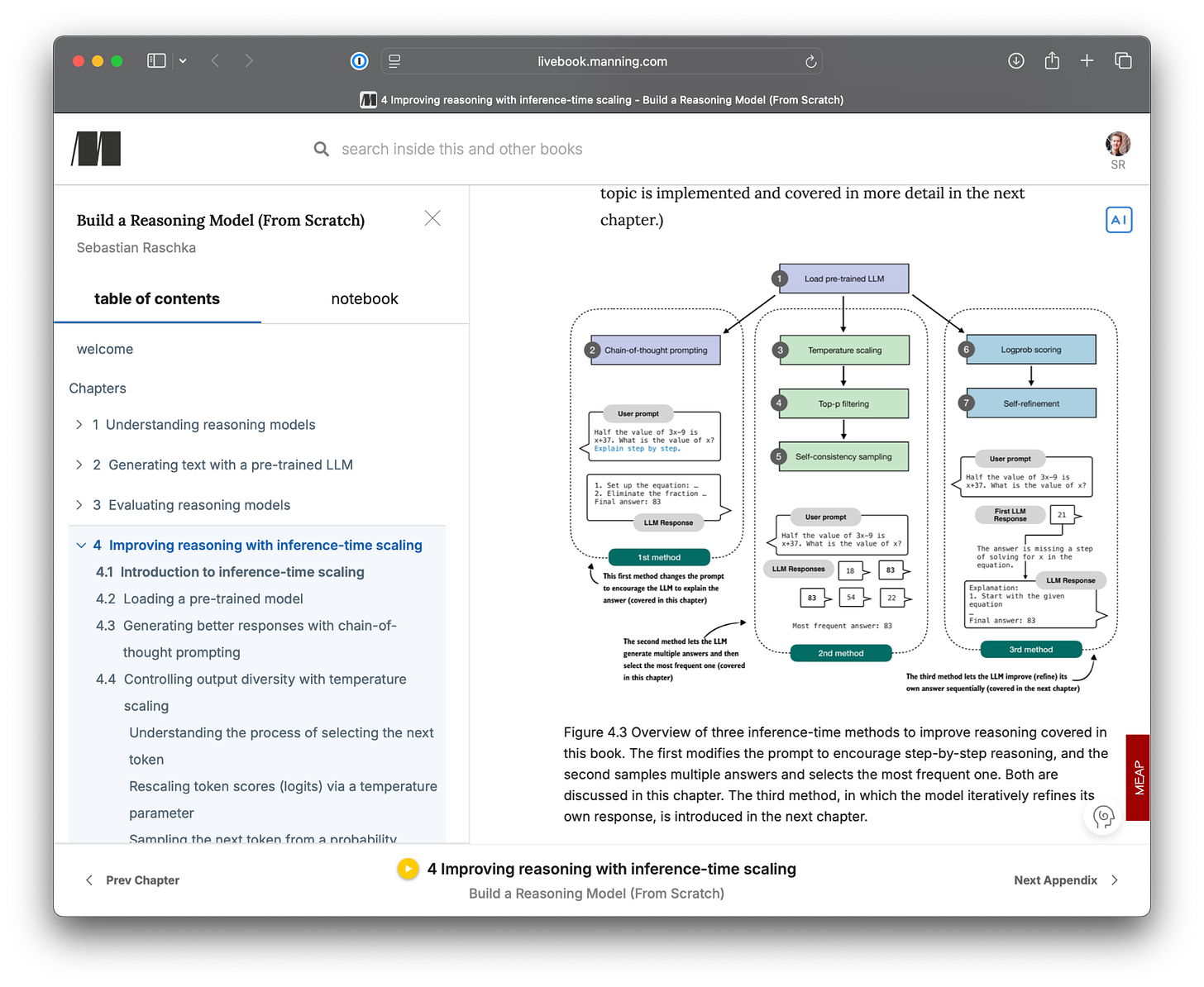

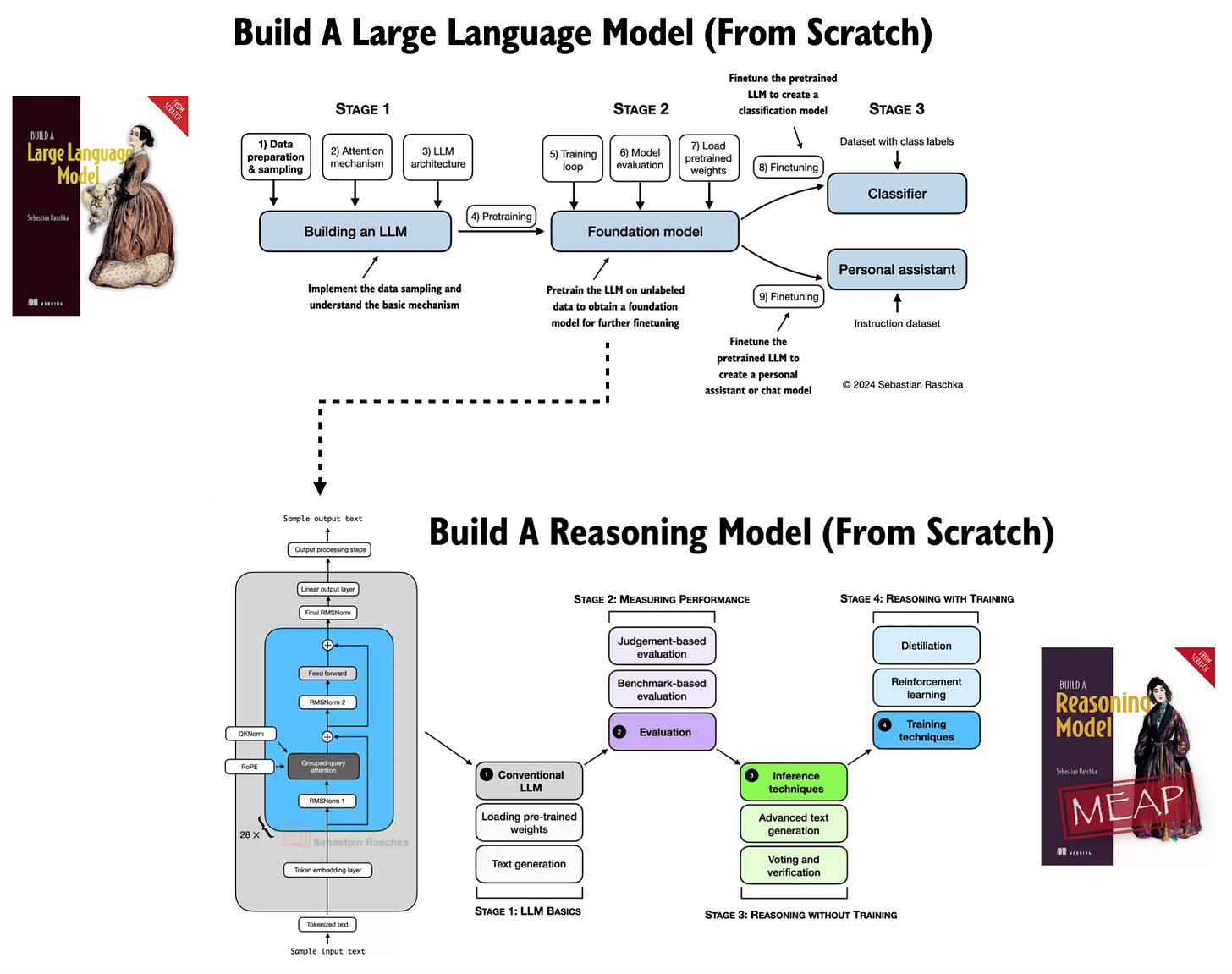

In addition, as you may know, I am currently working on a sequel, Build A Reasoning Model (From Scratch).

The first book, Build A Large Language Model (From Scratch), focuses on the core large language model architecture and the fundamentals of pre-training.

The reasoning model book then picks up where the first book leaves off. Starting from a pre-trained base model, it explores inference-time scaling methods and reinforcement learning techniques aimed specifically at improving reasoning capabilities.

Next to this Substack, I am working hard on writing the reasoning book, and in many ways, I think this is my most well thought-out and most polished book so far.

At this point, my estimate is that I spend approximately 75-120 hours on each chapter. In case you are curious, I estimate that this typically breaks down as follows:

3-5 hours: brainstorming and revising the topic selection

5-10 hours: structuring the content

20 hours: writing the initial code

10-20 hours: running additional experiments and reading the latest literature for more insights

10-20 hours: making figures

10 hours: writing the initial draft text

10-20 hours: rewriting and refining the chapter

5-10 hours: making the exercises plus running the experiments

2-5 hours: incorporating editor and reader suggestions

Currently, I am halfway through with chapter 6, which implements the reinforcement learning with verifiable rewards (GRPO) code for training reasoning models.

Build A Reasoning Model (From Scratch) is very hard work but I am thoroughly enjoying working on it! I hope you and other readers will find it useful similar to Build A Large Language Model (From Scratch)

9. Surprises in 2025 and Predictions for 2026

I wanted to close this article with some of the main takeaways, focusing on things that I think were a bit surprising to me, and things I predict for 2026.

9.1 Noteworthy and Surprising Things in 2025

Let’s start with the surprises of 2025. These are developments I likely would not have expected if you had asked me a year earlier in 2024:

Several reasoning models are already achieving gold-level performance in major math competitions (OpenAI with an unnamed model, Gemini Deep Think, and open-weight DeepSeekMath-V2). I am not surprised that this happened in general, but I am surprised that this already happened in 2025, not 2026.

Llama 4 (or Llama in general) fell almost completely out of favor in the open-weight community, and Qwen has overtaken Llama in popularity (as measured by the number of downloads and derivatives as reported via Nathan Lambert’s ATOM project).

Mistral AI uses the DeepSeek V3 architecture for its latest flagship Mistral 3 model, announced in December 2025.

Besides Qwen3 and DeepSeek R1/V3.2, many additional contenders have emerged in the race for open-weight state-of-the-art models, including Kimi, GLM, MiniMax, and Yi.

Cheaper, efficient hybrid architectures are already becoming a bigger priority in leading labs (Qwen3-Next, Kimi Linear, Nemotron 3) as opposed to being developed by separate labs

OpenAI released an open-weight model (gpt-oss, and I wrote a standalone article about it earlier this year).

MCP (joining the Linux Foundation) has already become the standard for tool and data access in agent-style LLM systems (for now); I expected the ecosystem to remain more fragmented in 2025, until at least 2026.

9.2 Predictions for 2026

We will likely see an industry-scale, consumer-facing diffusion model for cheap, reliable, low-latency inference, with Gemini Diffusion probably going first.

The open-weight community will slowly but steadily adopt LLMs with local tool use and increasingly agentic capabilities.

RLVR will more widely expand into other domains beyond math and coding (for example, chemistry, biology, and others).

Classical RAG will slowly fade as a default solution for document queries. Instead of using retrieval on every document-related query, developers will rely more on better long-context handling, especially as there are going to be better “small” open-weight models.

A lot of LLM benchmark and performance progress will come from improved tooling and inference-time scaling rather than from training or the core model itself. It will look like LLMs are getting much better, but this will mainly be because the surrounding applications are improving. At the same time, developers will focus more on lowering latency and making reasoning models expand fewer reasoning tokens where it is unnecessary. Don’t get me wrong, 2026 will push the state-of-the-art further, but the proportion of progress will come more from the inference than purely the training side this year.

To wrap things up, I think if there is one meta-lesson from 2025, it is that progress in LLMs is less about a single breakthrough, and improvements are being made on multiple fronts via multiple independent levers. This includes architecture tweaks, data quality improvements, reasoning training, inference scaling, tool calling, and more.

At the same time, evaluation remains hard, benchmarks are imperfect, and good judgment about when and how to use these systems is still essential.

My hope for 2026 is that we continue to see interesting improvements, but also that we understand where the improvements are coming from. This requires both better and more consistent benchmarking, and of course transparency.

Thank you for reading, and for all the thoughtful feedback and discussions throughout the year, in the comments and across all the different platforms, from Substack Notes to GitHub.

The positive feedback and detailed conversations genuinely keep me motivated to invest the time and energy required for long-form articles and to keep digging deeply into LLM research and implementation details. I learned a lot from these exchanges, and I hope you did too.

I am very much looking forward to continuing these conversations as the field keeps evolving in 2026!

Cheers,

Sebastian

10. Bonus: A Curated LLM Research Papers List (July to December 2025)

In June, I shared a bonus article with my curated and bookmarked research paper lists to the paid subscribers who make this Substack possible.

In a similar fashion, as a thank you to all the kind supporters, below, I prepared a list of all the interesting research articles I bookmarked and categorized from July to December 2025. I skimmed over the abstracts of these papers but only read a very small fraction. However, I still like to keep collecting these organized lists as I often go back to sets of them when working on a given project.

However, given the already enormous length of this current article, I am sharing this list in a separate article, which is linked below:

Thanks so much for subscribing to my Ahead of AI blog and for supporting my work this year. I really appreciate it. Your support makes this work feasible in a very real sense and allows me to keep spending the time needed to write, experiment, and think deeply about these topics!

Thank You for investing so much time and effort in this! I personally have learnt so much from your content. I got introduced to your content when my Professor used your LLM from Scratch book as the primary textbook for the new Introductions to LLMs Course in our college. Your open educational resources are really helping many students grow and helping the community take many steps forward worldwide. I know many people who I am sure will hold similar views. Thank You for keeping so much knowledge so very accessible! Love from India

Excellent reading for the end of the year! Thank you!