From DeepSeek V3 to V3.2: Architecture, Sparse Attention, and RL Updates

Understanding How DeepSeek's Flagship Open-Weight Models Evolved

Last updated: January 1st, 2026

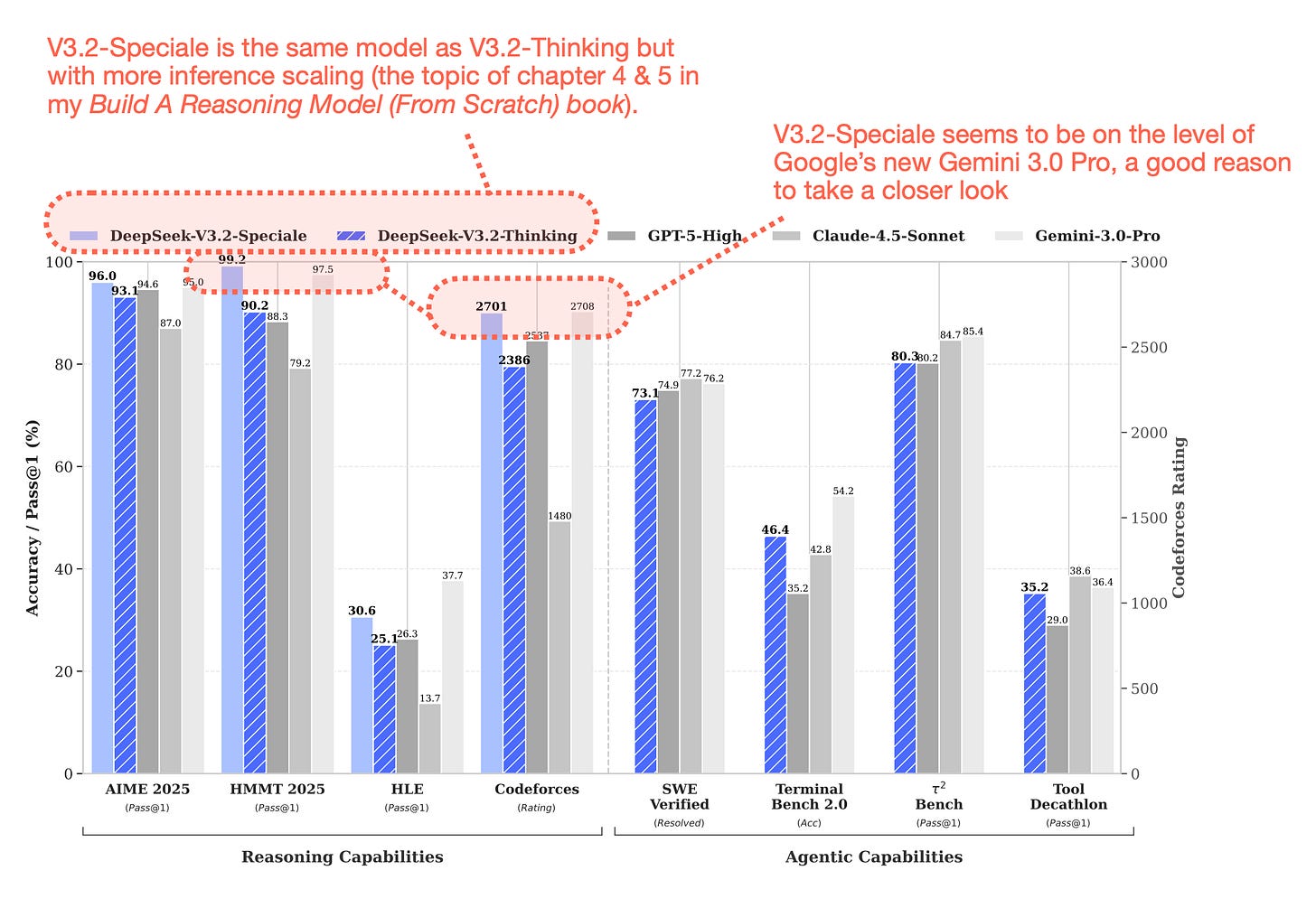

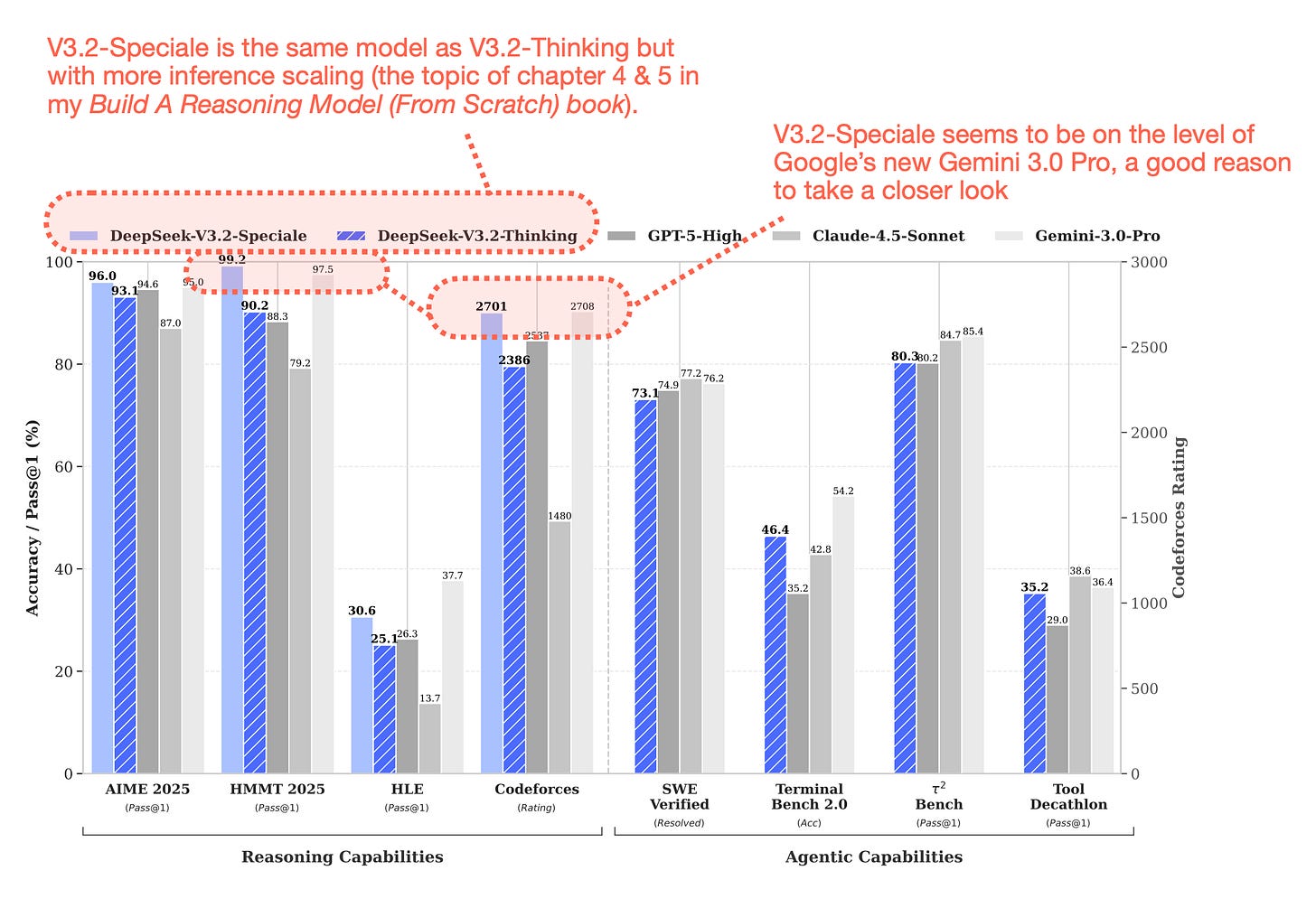

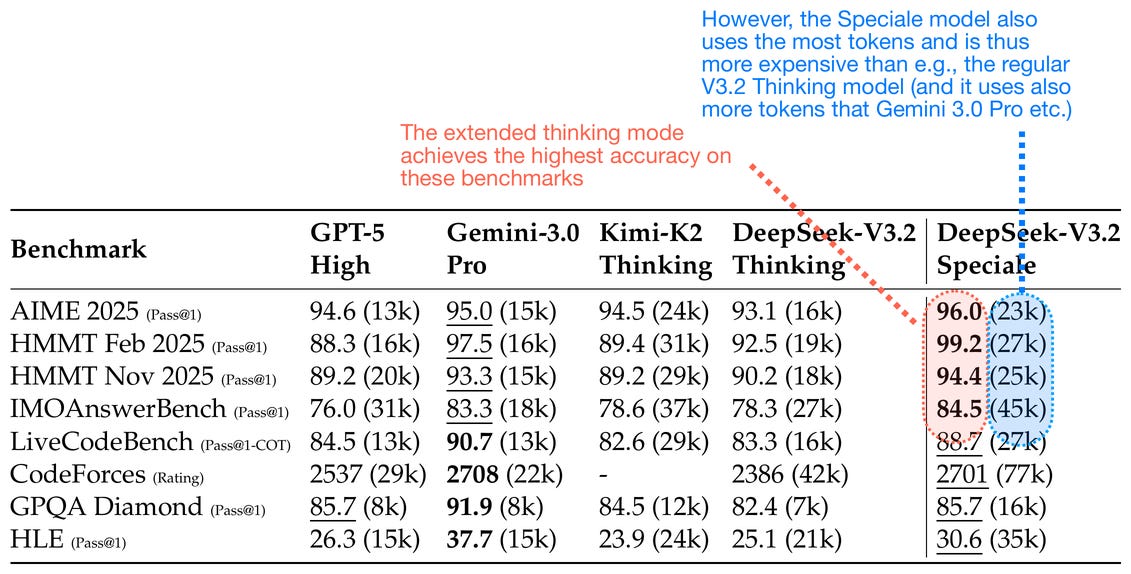

Similar to DeepSeek V3, the team released their new flagship model over a major US holiday weekend. Given DeepSeek V3.2’s really good performance (on GPT-5 and Gemini 3.0 Pro) level, and the fact that it’s also available as an open-weight model, it’s definitely worth a closer look.

I covered the predecessor, DeepSeek V3, at the very beginning of my The Big LLM Architecture Comparison article, which I kept extending over the months as new architectures got released. Originally, as I just got back from Thanksgiving holidays with my family, I planned to “just” extend the article with this new DeepSeek V3.2 release by adding another section, but I then realized that there’s just too much interesting information to cover, so I decided to make this a longer, standalone article.

There’s a lot of interesting ground to cover and a lot to learn from their technical reports, so let’s get started!

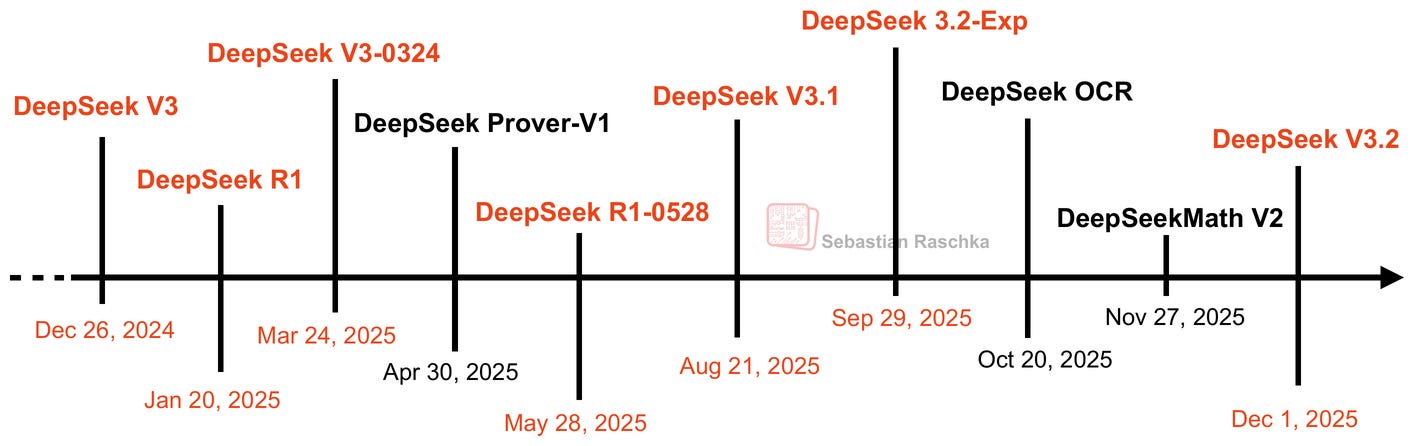

1. The DeepSeek Release Timeline

While DeepSeek V3 wasn’t popular immediately upon release in December 2024, the DeepSeek R1 reasoning model (based on the identical architecture, using DeepSeek V3 as a base model) helped DeepSeek become one of the most popular open-weight models and a legit alternative to proprietary models such as the ones by OpenAI, Google, xAI, and Anthropic.

So, what’s new since V3/R1? I am sure that the DeepSeek team has been super busy this year. However, there hasn’t been a major release in the last 10-11 months since DeepSeek R1.

Personally, I think it’s reasonable to go ~1 year for a major LLM release since it’s A LOT of work. However, I saw on various social media platforms that people were pronouncing the team “dead” (as a one-hit wonder).

I am sure the DeepSeek team has also been busy navigating the switch from NVIDIA to Huawei chips. By the way, I am not affiliated with them or have spoken with them; everything here is based on public information. As far as I know, they are back to using NVIDIA chips.

Finally, it’s also not that they haven’t released anything. There have been a couple of smaller releases that trickled in this year, for instance, DeepSeek V3.1 and V3.2-Exp.

As I predicted back in September, the DeepSeek V3.2-Exp release was intended to get the ecosystem and inference infrastructure ready to host the just-released V3.2 model.

V3.2-Exp and V3.2 use a non-standard sparse attention variant that requires custom code, but more on this mechanism later. (I was tempted to cover it in my previous Beyond Standard LLMs article, but Kimi Linear was released around then, which I prioritized for this article section on new attention variants.)

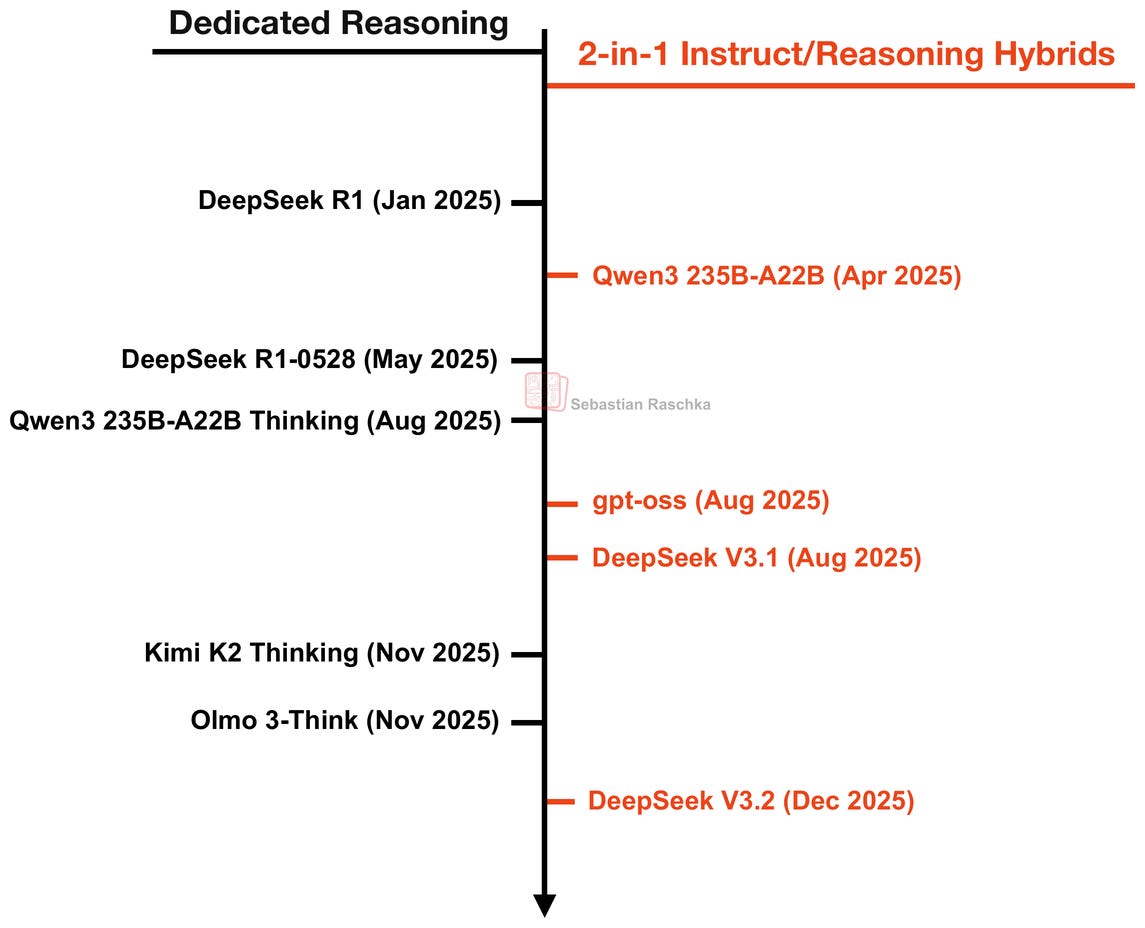

2. Hybrid Versus Dedicated Reasoning Models

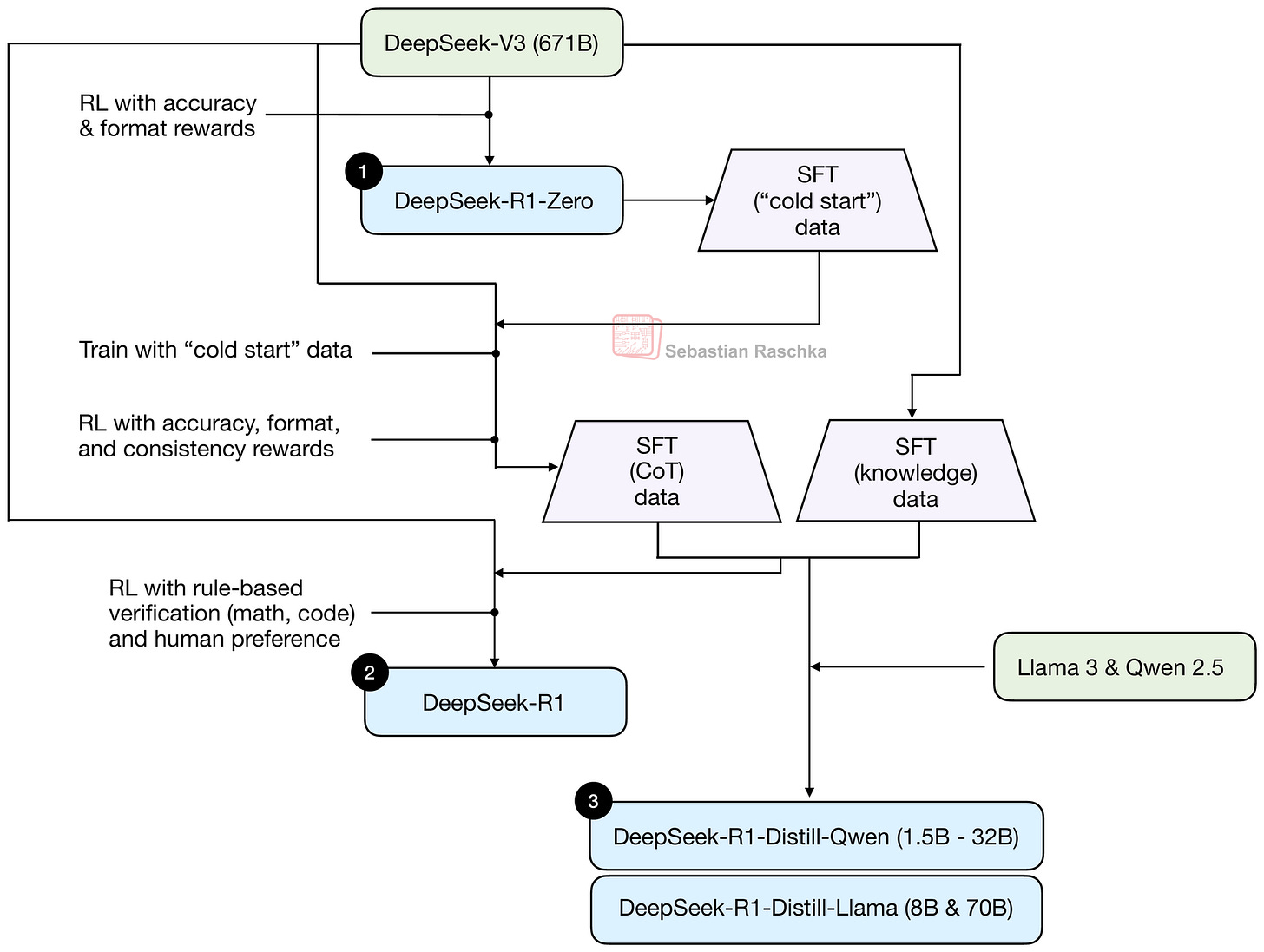

Before discussing further model details, it might be worthwhile to discuss the overall model types. Originally, DeepSeek V3 was released as a base model, and DeepSeek R1 added additional post-training to develop a dedicated reasoning model. This procedure is summarized in the figure below.

You can read more about the training pipeline in the figure above in my Understanding Reasoning LLMs article.

What’s worthwhile noting here is that DeepSeek V3 is a base model, and DeepSeek R1 is a dedicated reasoning model.

In parallel with DeepSeek, other teams have also released many really strong open-weight reasoning models. One of the strongest open-weight models this year was Qwen3. Originally, it was released as a hybrid reasoning model, which means that users were able to toggle between reasoning and non-reasoning modes within the same model. (In the case of Qwen3, this toggling was enabled via the tokenizer by adding/omitting <think></think> tags.)

Since then, LLM teams have released (and in some cases gone back and forth between) both dedicated reasoning models and Instruct/Reasoning hybrid models, as shown in the timeline below.

For instance, Qwen3 started out as a hybrid model, but the Qwen team then later released separate instruct and reasoning models as they were easier to develop and yielded better performance in each respective use case.

Some models like OpenAI’s gpt-oss only come in a hybrid variant where users can choose the reasoning effort via a system prompt (I suspect this is handled similarly in GPT-5 and GPT-5.1).

And in the case of DeepSeek, it looks like they moved in the opposite direction from a dedicated reasoning model (R1) to a hybrid model (V3.1 and V3.2). However, I suspect that R1 was mainly a research project to develop reasoning methods and the best reasoning model at the time. The V3.2 release may be more about developing the best overall model for different use cases. (Here, R1 was more like a testbed or prototype model.)

And I also suspect that, while the DeepSeek team developed V3.1 and V3.2 with reasoning capabilities, they might still be working on a dedicated R2 model.

3. From DeepSeek V3 to V3.1

Before discussing the new DeepSeek V3.2 release in more detail, I thought it would be helpful to start with an overview of the main changes going from V3 to V3.1.

3.1 DeepSeek V3 Overview and Multi-Head Latent Attention (MLA)

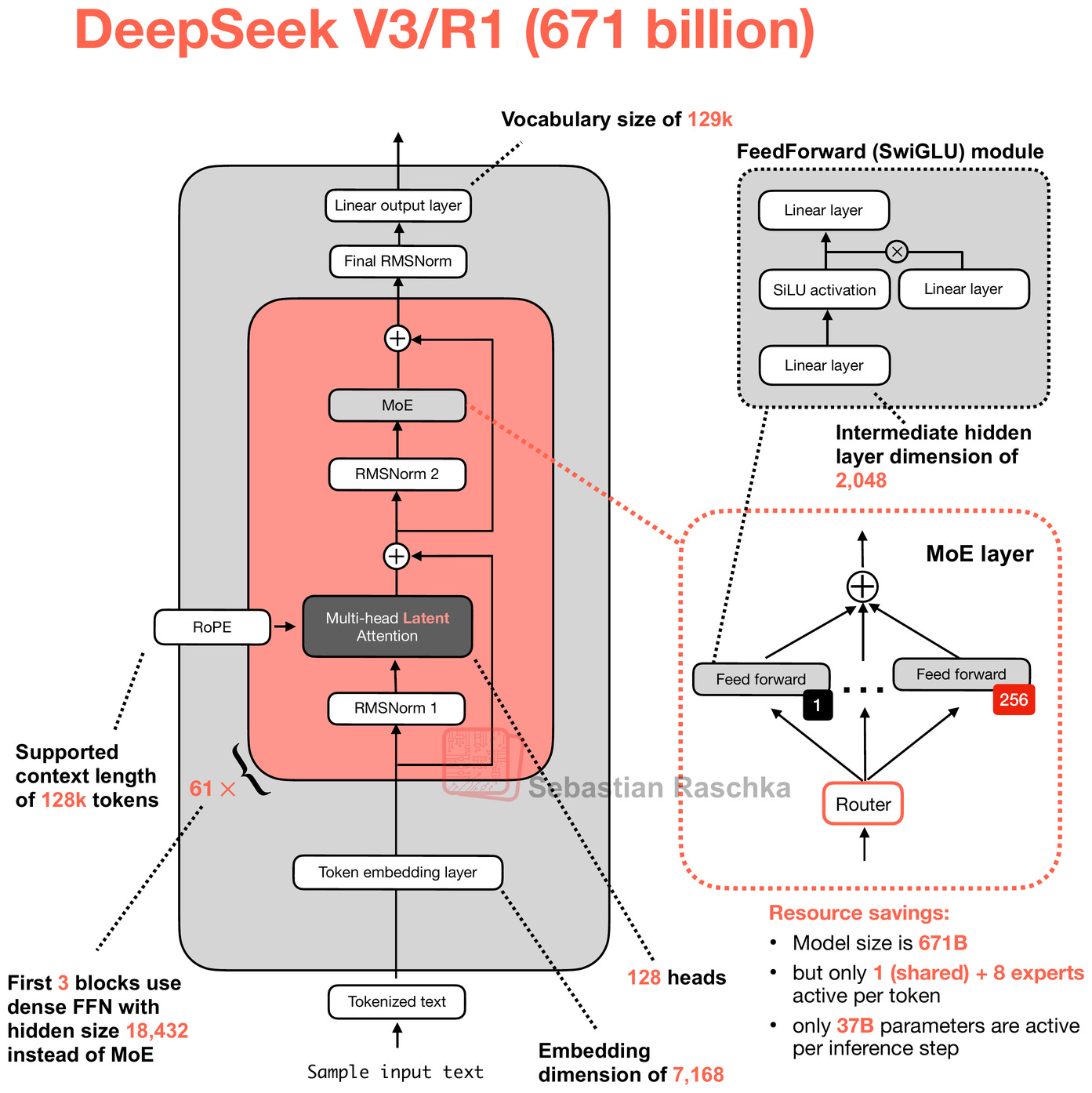

I already discussed DeepSeek V3 and R1 in great detail in several other articles. To summarize the main points, DeepSeek V3 is a base model that uses two noteworthy architecture aspects: Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) and Multi-Head Latent Attention (MLA).

I think you are probably well familiar with MoE at this point, so I am skipping the introduction here. However, if you want to read more, I recommend the short overview in my The Big Architecture Comparison article for more context.

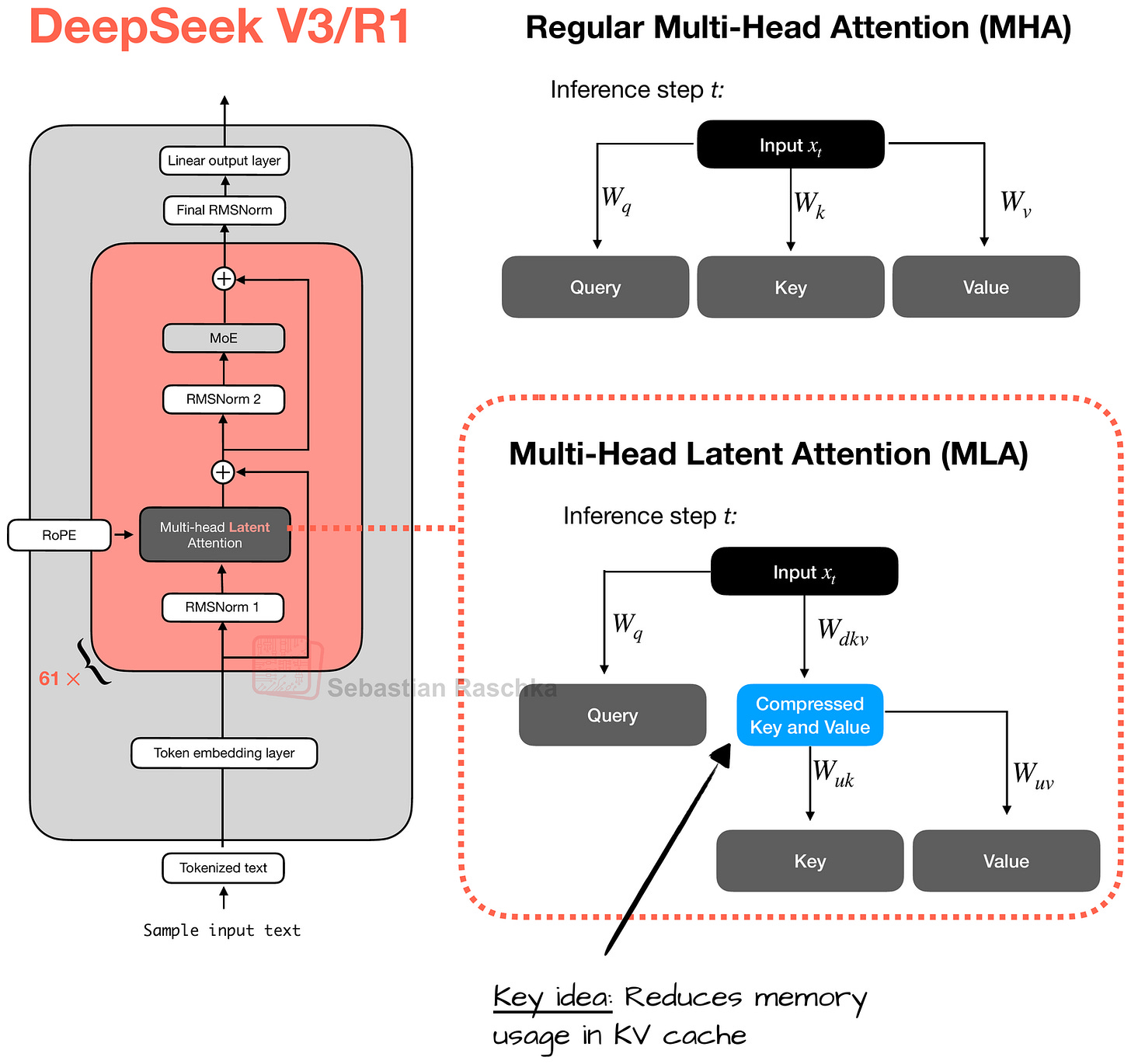

The other noteworthy highlight is the use of MLA. MLA, which is used in DeepSeek V2, V3, and R1, offers a memory-saving strategy that pairs particularly well with KV caching. The idea in MLA is that it compresses the key and value tensors into a lower-dimensional space before storing them in the KV cache.

At inference time, these compressed tensors are projected back to their original size before being used, as shown in the figure below. This adds an extra matrix multiplication but reduces memory usage.

(As a side note, the queries are also compressed, but only during training, not inference.)

The figure above illustrates the main idea behind MLA, where the keys and values are first projected into a latent vector, which can then be stored in the KV cache to reduce memory requirements. This requires a later up-projection back into the original key-value space, but overall it improves efficiency (as an analogy, you can think of the down- and up-projections in LoRA).

Note that the query is also projected into a separate compressed space, similar to what’s shown for the keys and values. However, I omitted it in the figure above for simplicity.

By the way, as mentioned earlier, MLA is not new in DeepSeek V3, as its DeepSeek V2 predecessor also used (and even introduced) it.

3.2 DeepSeek R1 Overview and Reinforcement Learning with Verifiable Rewards (RLVR)

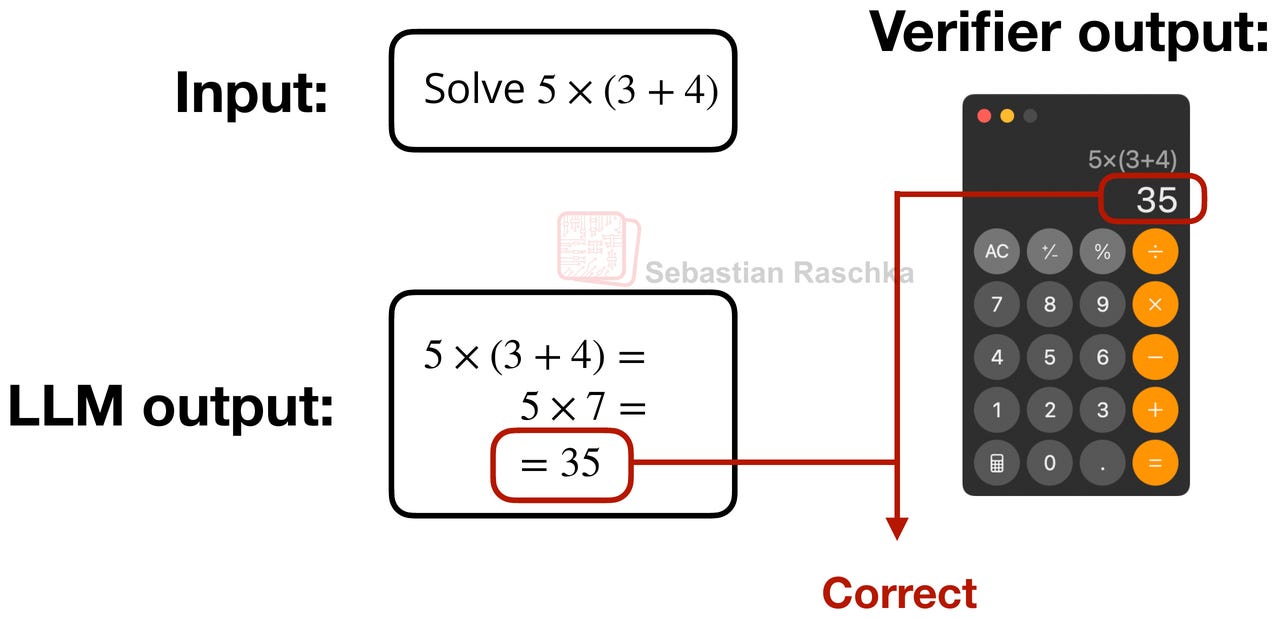

DeepSeek R1 uses the same architecture as DeepSeek V3 above. The difference is the training recipe. I.e., using DeepSeek V3 as the base model, DeepSeek R1 was focused on the Reinforcement Learning with Verifiable Rewards (RLVR) method to improve the reasoning capabilities of the model.

The core idea in RLVR is to have the model learn from responses that can be verified symbolically or programmatically, such as math and code (but this can, of course, also be extended beyond these two domains).

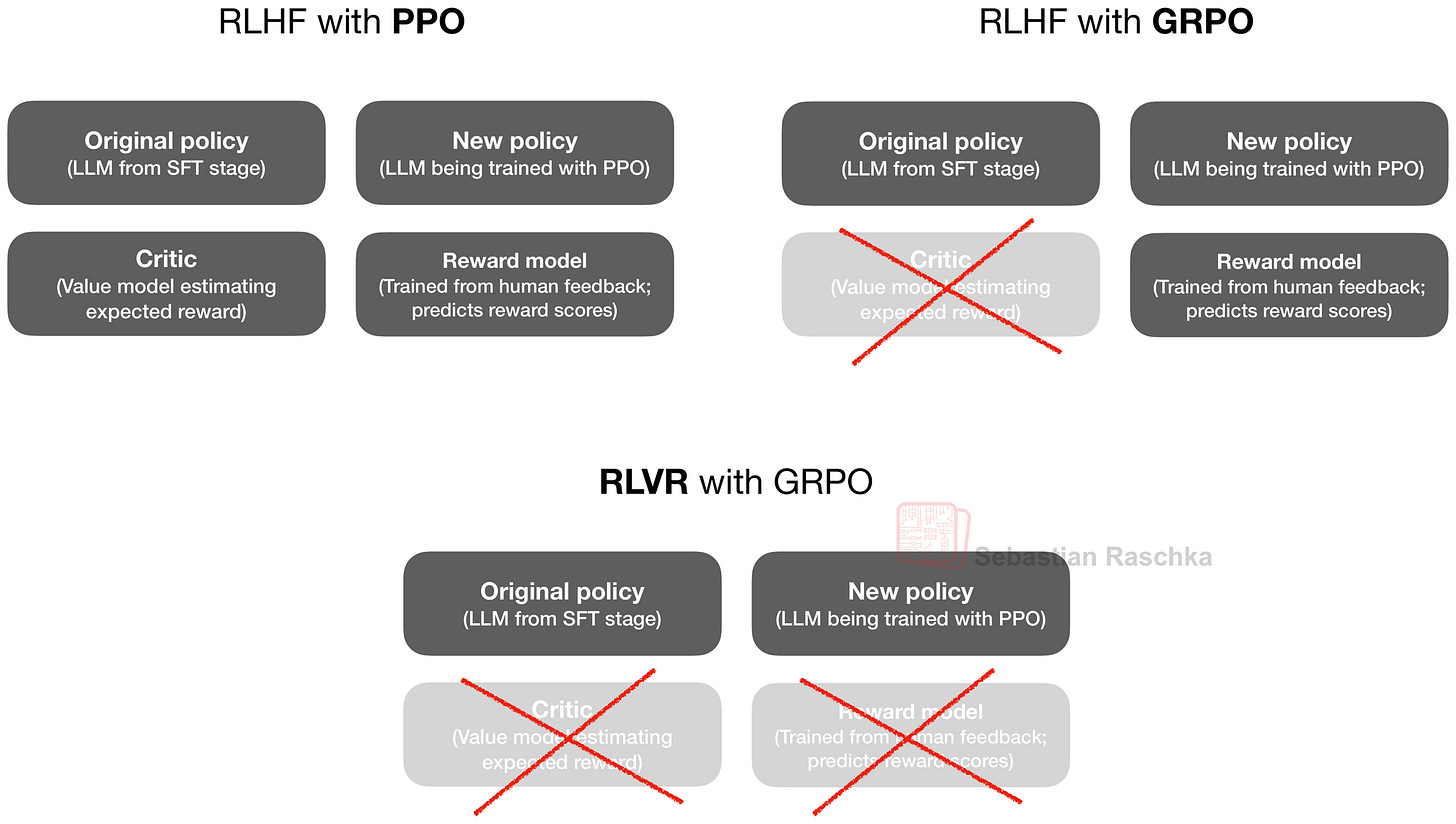

The GRPO algorithm, which is short for Group Relative Policy Optimization, is essentially a simpler variant of the Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) algorithm that is popular in Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback (RLHF), which is used for LLM alignment.

I covered the RLVR training with their GRPO algorithm in more detail (including the math behind it) in my The State of Reinforcement Learning for LLM Reasoning if you are interested in additional information.

3.3 DeepSeek R1-0528 Version Upgrade

As the DeepSeek team stated themselves, DeepSeek R1-0528 is basically a “minor version upgrade.”

The architecture remains the same as in DeepSeek V3/R1, and the improvements are on the training side to bring it up to par with OpenAI o3 and Gemini 2.5 Pro at the time.

Unfortunately, the DeepSeek team didn’t release any specific information describing how this was achieved; however, they stated that it partly comes from optimizations in their post-training pipeline. Also, based on what’s been shared, I think it’s likely that the hosted version of the model uses more computational resources at inference time (longer reasoning).

3.4 DeepSeek V3.1 Hybrid Reasoning

DeepSeek V3.1 is a hybrid model with both general chat (instruct) and reasoning capabilities. I.e., instead of developing two separate models, there is now one model in which users can switch modes via the chat prompt template (similar to the initial Qwen3 model).

DeepSeek V3.1 is based on DeepSeek V3.1-Base, which is in turn based on DeepSeek V3. They all share the same architecture.

4. DeepSeek V3.2-Exp and Sparse Attention

DeepSeek V3.2-Exp (Sep 2025) is where it gets more interesting.

Originally, the DeepSeek V3.2-Exp didn’t top the benchmarks, which is why there wasn’t as much excitement around this model upon release. However, as I speculated back in September, this was likely an early, experimental release to get the infrastructure (especially the inference and deployment tools) ready for a larger release, since there are a few architectural changes in DeepSeek V3.2-Exp. The bigger release is DeepSeek V3.2 (not V4), but more on that later.

So, what’s new in DeepSeek V3.2-Exp? First, DeepSeek V3.2-Exp was trained based on DeepSeek V3.1-Terminus as a base model. What’s DeepSeek V3.1-Terminus? It’s just a small improvement over the DeepSeek V3.1 checkpoint mentioned in the previous section.

The technical report states that:

DeepSeek-V3.2-Exp, an experimental sparse-attention model, which equips

DeepSeek-V3.1-Terminus with DeepSeek Sparse Attention (DSA) through continued training. With DSA, a fine-grained sparse attention mechanism powered by a lightning indexer, DeepSeek-V3.2-Exp achieves significant efficiency improvements in both training and inference, especially in long-context scenarios.

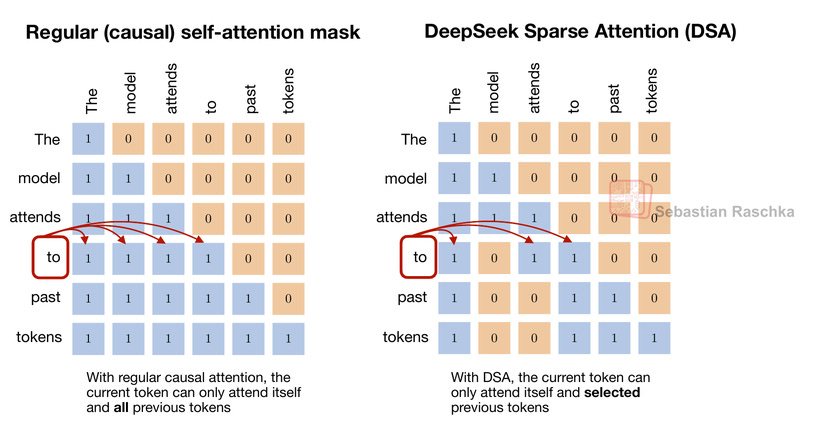

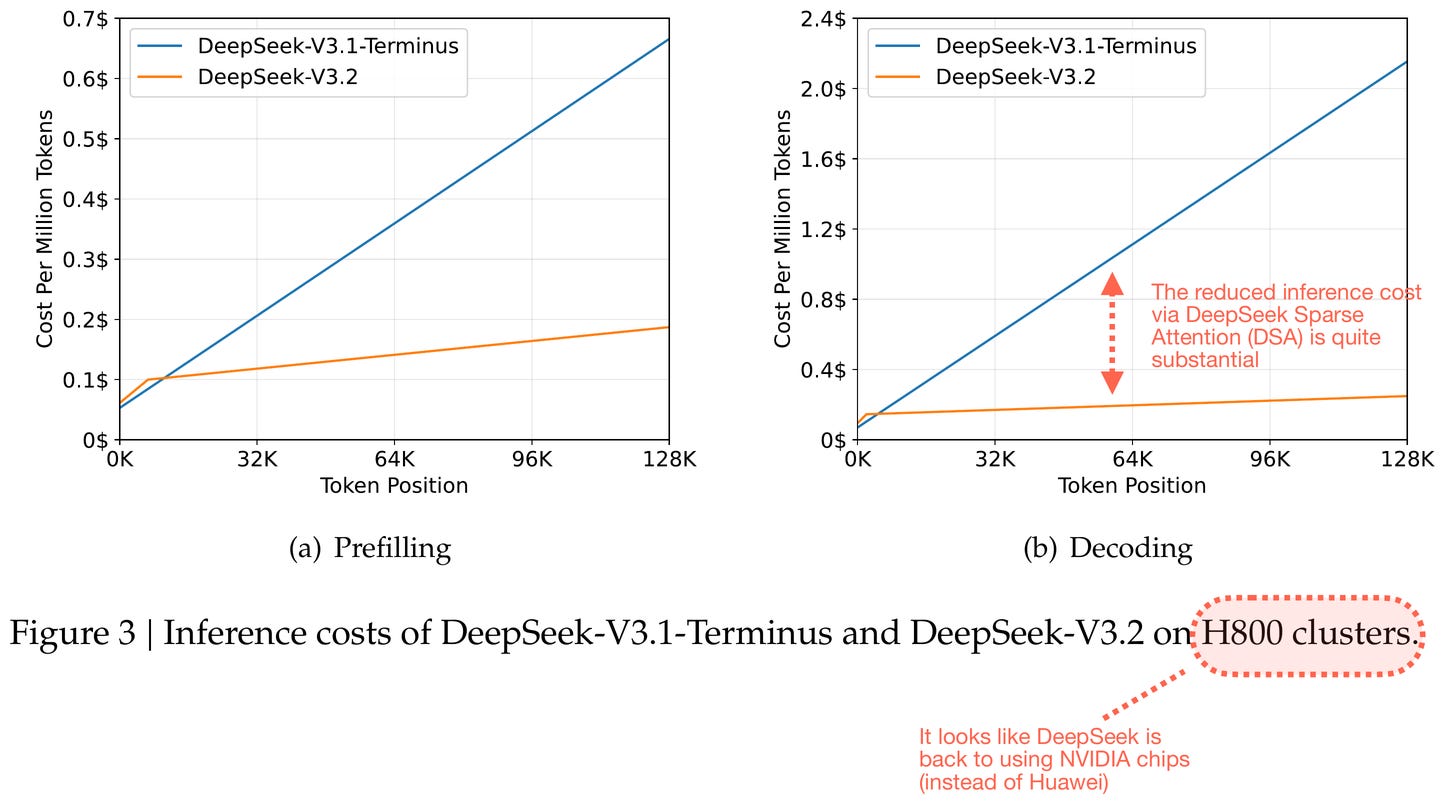

As the paragraph above states, the main innovation here is the DeepSeek Sparse Attention (DSA) mechanism that they add to DeepSeek V3.1-Terminus before doing further training on that checkpoint.

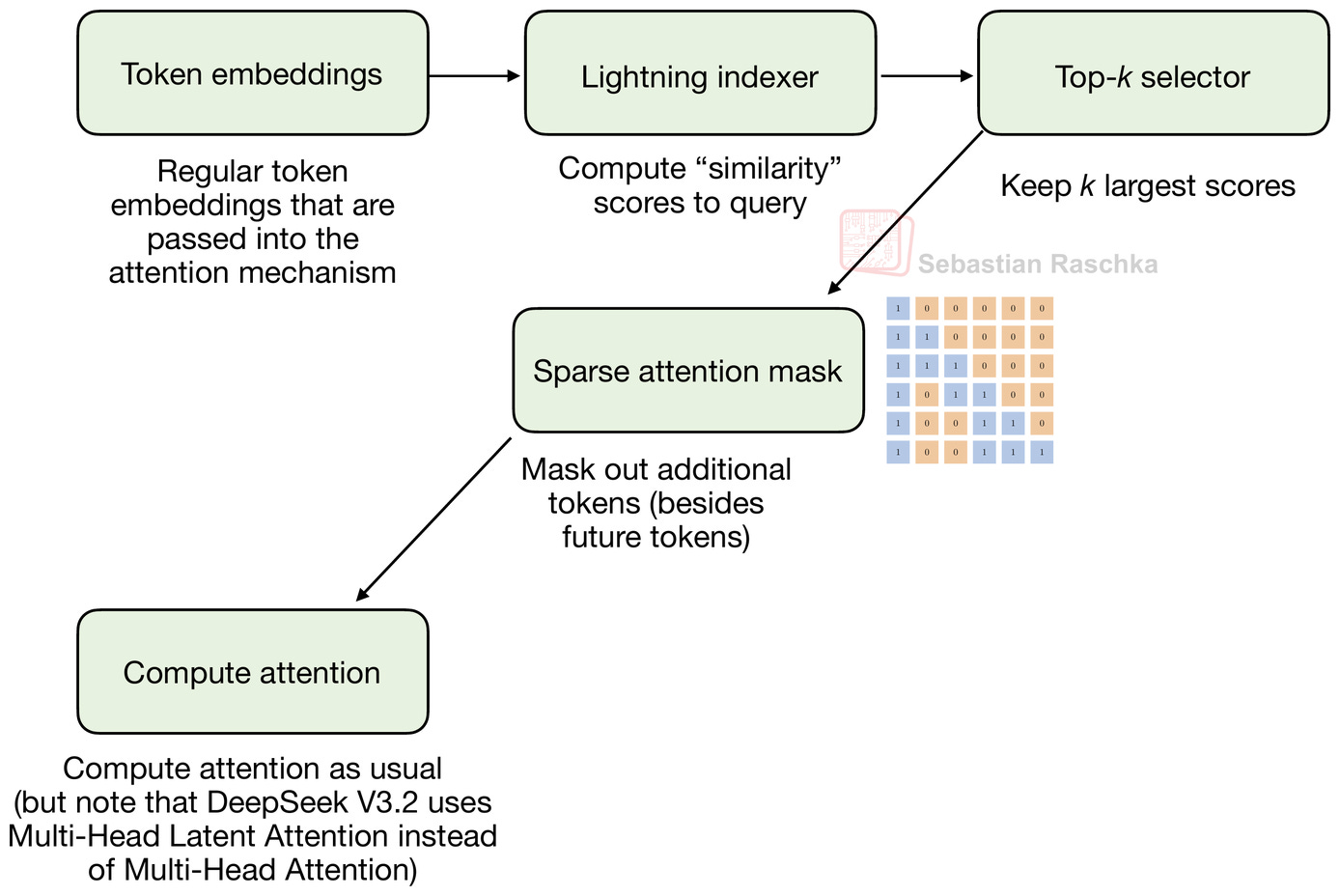

This DSA consists of (1) a lightning indexer and (2) a token-selector, and the goal is to selectively reduce the context to improve efficiency.

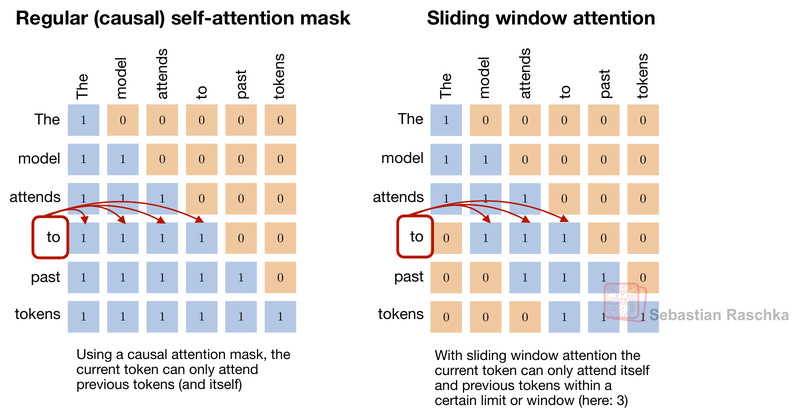

To explain how it works, let’s start with sliding-window attention. For instance, sliding window attention is a technique (recently used by Gemma 3 and Olmo 3) that limits the attention window to a fixed size, as illustrated in the figure below.

DSA is based on the same idea as sliding-window attention: only a subset of past tokens can be attended to. However, instead of selecting the tokens that can be attended via a fixed-width sliding window, DSA has an indexer and token selector to decide which past tokens can be attended. In other words, the tokens that can be attended are more random, as illustrated in the figure below.

However, while I said “random” above, the pattern of which past tokens are selected is not actually random but learned.

In practice, DSA uses its so-called lightning indexer to compute relevance scores for each new query token based on all previous tokens. For this computation, the lightning indexer uses the compressed token representations in DeepSeek’s Multi-Head Latent Attention (MLA) and computes the token similarity towards other tokens. The similarity score is basically a scaled dot product between query and key vectors passed through a ReLU function.

If you are interested in the mathematical details, the equation (taken from the paper) for this lightning indexer similarity score is shown below:

Here, w is a learned per-head weighting coefficient that determines how much each indexer head should contribute to the final similarity score. The q refers to the query, and the k refers to the key vector. And below is a list of the different subscripts:

t: position of the current query token;

s: position of a previous token in the sequence (0 ≤ s < t);

j: the index over the different indexer heads (Figure 10 above only showed one head for simplicity), so qt, j means “query vector for current token t in indexer head j“.

You may notice that the indexer is only over the queries, not the keys. That’s because the model only needs to decide which past tokens each new query should consider. The keys are already compressed and stored in the KV cache, so the indexer does not need to score or compress them again over the different heads.

The ReLU function here, since it’s f(x) = max(x, 0), zeroes negative dot-product positions, which could theoretically enable sparsity, but since there is a summation over the different heads, it’s unlikely that the indexer score is actually 0. The sparsity rather comes from the separate token selector.

The separate token selector keeps only a small number of high-scoring tokens (for example, the top-k positions) and constructs a sparse attention mask that masks out the other tokens that are not contained in the selected subset. (The k in top-k, not to be confused with the k that is used for the keys in the equation above, is a hyperparameter that is set to 2048 in the model code that the DeepSeek team shared.)

The figure below illustrates the whole process in a flowchart.

To sum it up, the indexer and token selector result in each token attending to a few past tokens that the model has learned to consider most relevant, rather than all tokens or a fixed local window.

The goal here was not to improve the performance over DeepSeek V3.1-Terminus but to reduce the performance degradation (due to the sparse attention mechanism) while benefiting from improved efficiency.

Overall, the DSA reduces the computational complexity of the attention mechanism from quadratic O(𝐿2), where L is the sequence length, to a linear O(𝐿𝑘), where 𝑘 (≪𝐿) is the number of selected tokens.

5. DeepSeekMath V2 with Self-Verification and Self-Refinement

Having discussed DeepSeek V3.2-Exp, we are getting closer to the main topic of this article: DeepSeek V3.2. However, there is one more puzzle piece to discuss first.

On November 27, 2025 (Thanksgiving in the US), and just 4 days before the DeepSeek V3.2 release, the DeepSeek team released DeepSeekMath V2, based on DeepSeek V3.2-Exp-Base.

This model was specifically developed for math and achieved gold-level scores in several math competitions. Essentially, we can think of it as a proof (of concept) model for DeepSeek V3.2, introducing one more technique.

The key aspect here is that reasoning models (like DeepSeek R1 and others) are trained with an external verifier, and the model learns, by itself, to write explanations before arriving at the final answer. However, the explanations may be incorrect.

As the DeepSeek team succinctly states, the shortcomings of regular RLVR:

[...] correct answers don’t guarantee correct reasoning.

[...] a model can arrive at the correct answer through flawed logic or fortunate errors.

The other limitation of the DeepSeek R1 RLVR approach they aim to address is that:

[...] many mathematical tasks like theorem proving require rigorous step-by-step derivation rather than numerical answers, making final answer rewards inapplicable.

So, to improve upon these two shortcomings mentioned above, in this paper, they train two models:

An LLM-based verifier for theorem proving.

The main model, a proof-generator, uses the LLM-based verifier as a reward model (instead of a symbolic verifier).

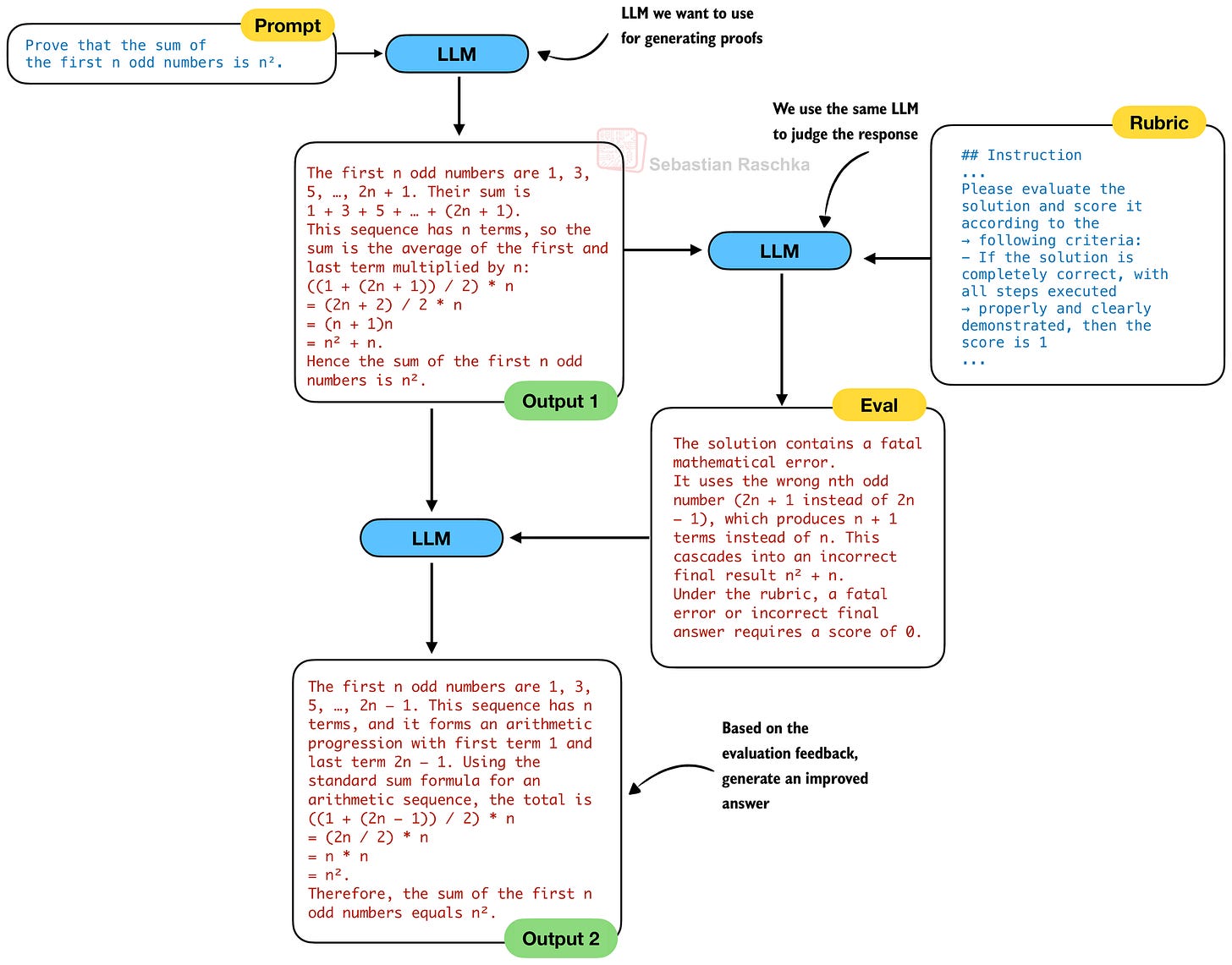

In addition to this self-verification via an LLM as described above, they also use self-refinement (covered in the upcoming Chapter 5 of my Build a Reasoning Model (From Scratch) book) to have the LLM iteratively improve its own answers.

5.1 Self-Verification

Having an LLM score for the intermediate steps is not new. There is a whole line of research on so-called process reward models, which have focused on this. Examples include Solving Math Word Problems With Process- and Outcome-based Feedback (2022) or Let’s Verify Step by Step (2023), but there are many more.

The challenges with process reward models are that it’s not easy to check whether intermediate rewards are correct, and it can also lead to reward hacking.

In the DeepSeek R1 paper in Jan 2025, they didn’t use process reward models as they found that:

its advantages are limited compared to the additional computational overhead it introduces during the large-scale reinforcement learning process in our experiments.

In this paper, they successfully revisit this in the form of self-verification. The motivation is that, even if no reference solution exists, humans can self-correct when reading proofs and identifying issues.

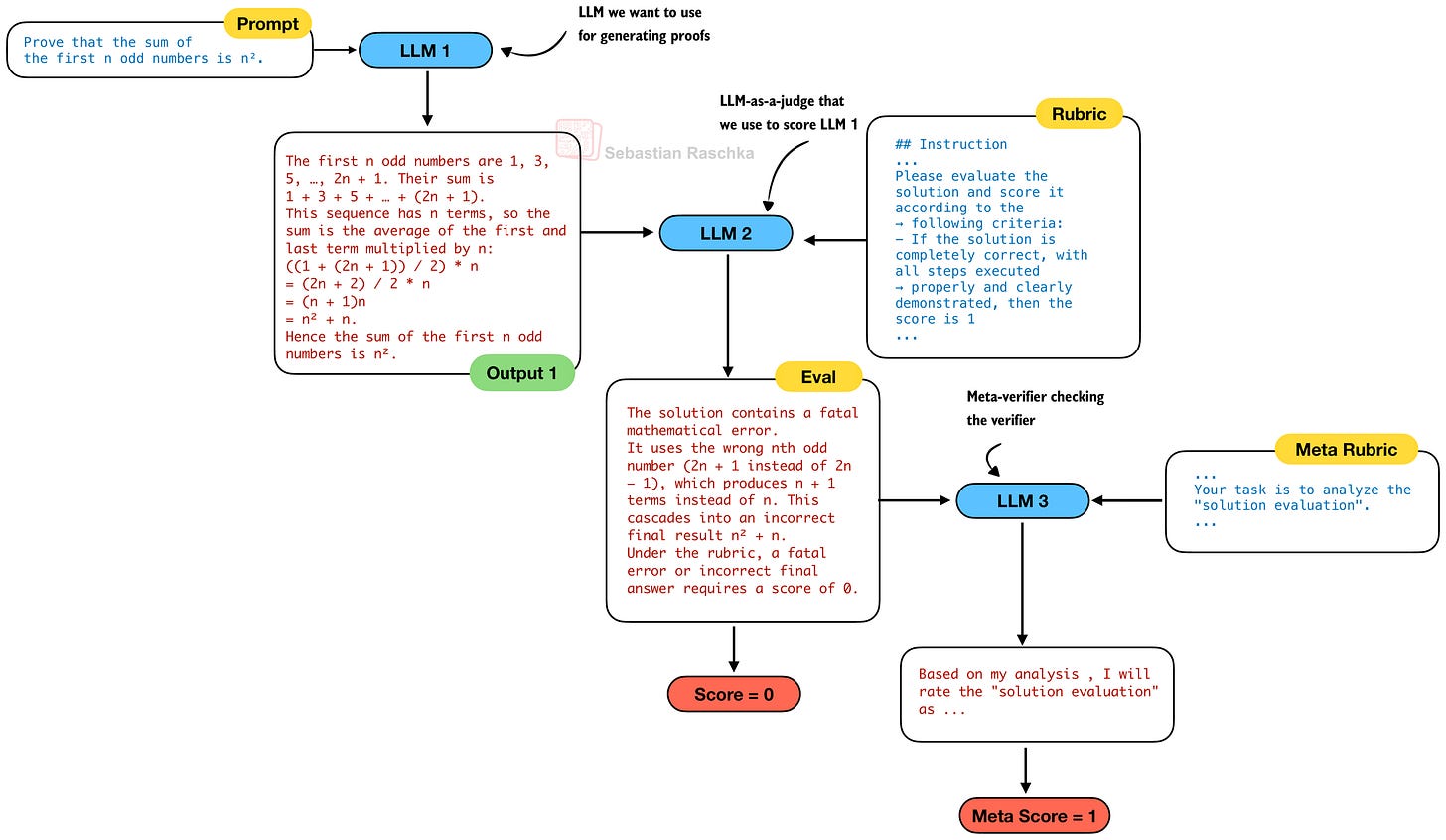

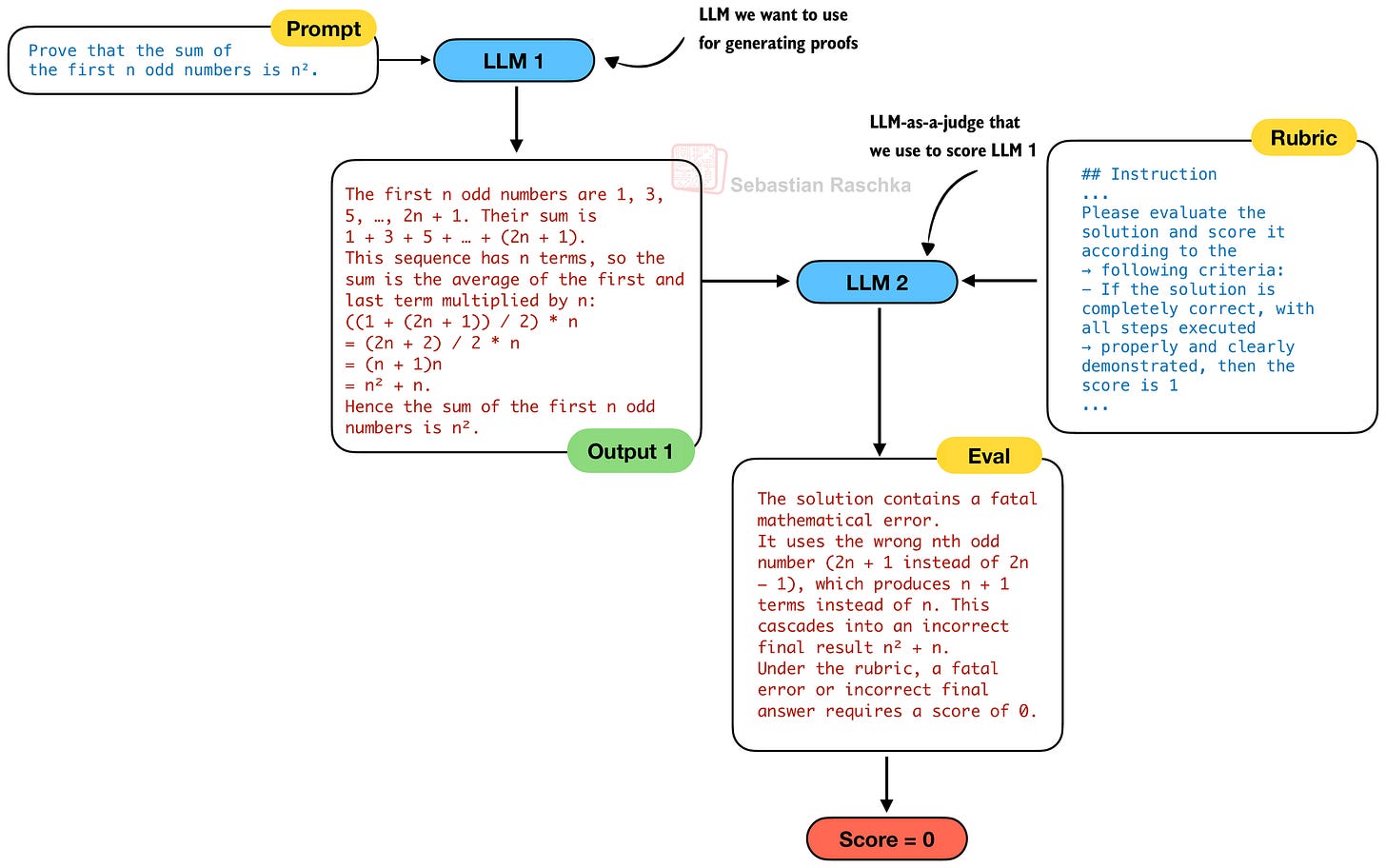

So, in order to develop a better model for writing mathematical proofs (LLM 1 in the figure below), they developed a proof verifier (LLM 2) in the figure below, which can be used as an LLM-as-a-judge to score the prover (LLM 1) outputs.

The verifier LLM (LLM 2) takes in a rubric to score the generated proof, where the score is

“1 for complete and rigorous proofs with all logical steps clearly justified;”

“0.5 for proofs with sound overall logic but minor errors or omitted details;”

“and 0 for fundamentally flawed proofs containing fatal logical errors or critical gaps.”

For the proof verifier model, they start with DeepSeek V3.2-Exp-SFT, a model they created based on DeepSeek V3.2-Exp by supervised fine-tuning on reasoning data (both math and code). They then further train the model with reinforcement learning using a format reward (a check whether the solution is in the expected format) and a score reward based on how close the predicted score is to the actual score (annotated by human math experts).

The goal of the proof verifier (LLM 2) is to check the generated proofs (LLM 1), but who checks the proof verifier? To make the proof verifier more robust and prevent it from hallucinating issues, they developed a third LLM, a meta-verifier.

The meta-verifier (LLM 3) is also developed with reinforcement learning, similar to LLM 2. While the use of a meta-verifier is not required, the DeepSeek team reported that:

the average quality score of the verifier’s proof analyses – as evaluated by the meta-verifier – improved from 0.85 to 0.96, while maintaining the same accuracy in proof score prediction.

This is actually quite an interesting setup. If you are familiar with generative adversarial networks (GANs), you may see the analogy here. For instance, the proof verifier (think of it as a GAN discriminator) improves the proof generator, and the proof generator generates better proofs, further pushing the proof verifier.

The meta score is used during training of the verifier (LLM 2) and the generator (LLM 1). It is not used at inference time in the self‑refinement loop, which we will discuss in the next section.

5.2 Self-Refinement

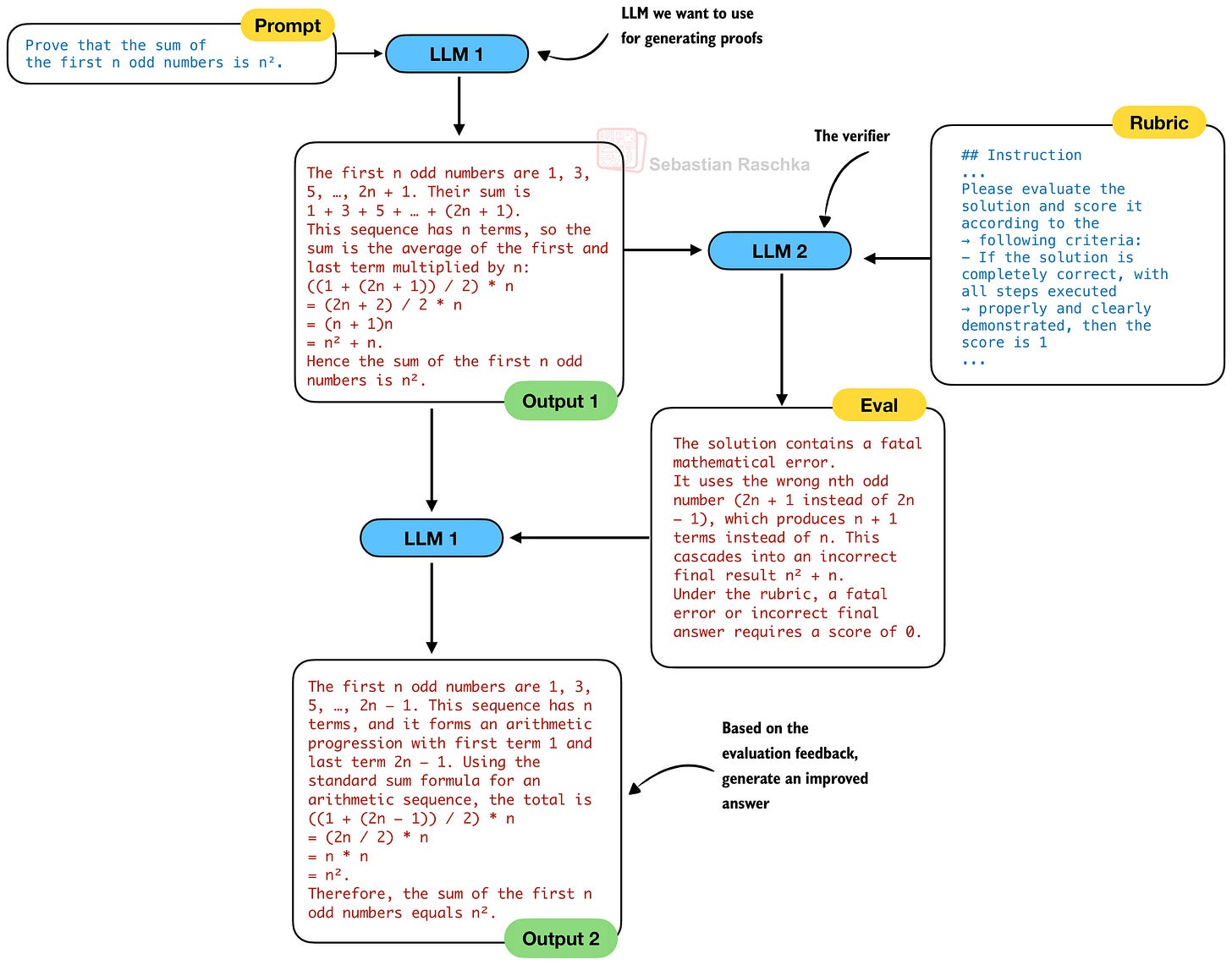

In the previous section, we talked about self-verification, i.e., analyzing the quality of the solution. The purpose of this is to implement self-refinement, which means that the LLM can act upon the feedback and revise its answer.

Traditionally, in self-refinement, which is an established and popular inference-scaling technique, we would use the same LLM for generating the solution and verifying it, before refining it. In other words, in the previous figures 12 and 13, LLM 1 and LLM 2 would be the same LLM. So, a traditional self-refinement process would look as follows:

However, the DeepSeek team observed a crucial issue with using the same LLM for both the generation and verification in practice:

when prompted to both generate and analyze its own proof in one shot, the generator tends to claim correctness even when the external verifier easily identify flaws. In other words, while the generator can refine proofs based on external feedback, it fails to evaluate its own work with the same rigor as the dedicated verifier.

As a logical consequence, one would assume they use a separate proof generator (LLM 1) and proof verifier (LLM 2). So, the self-refinement loop used here becomes similar to the one shown in the figure below. Note that we omit LLM 3, which is only used during the development of the verifier (LLM 2).

However, in practice, and different from Figure 15, the DeepSeek team uses the same generator and verifier LLM as in a classic self-refinement loop in Figure 14:

“All experiments used a single model, our final proof generator, which performs both proof generation and verification.”

In other words the separate verifier is essential for training, to improve the generator, but it is not used (/needed) later during inference once the generator is strong enough. And the key difference from naive single‑model self‑refinement is that the final prover has been trained under the guidance of a stronger verifier and meta‑verifier, so it has learned to apply those rubrics to its own outputs.

Also, using this 2-in-1 DeepSeekMath V2 verifier during inference is also beneficial in terms of resource and cost, as it add less complexity and compute requirements than running a second LLM for proof verification.

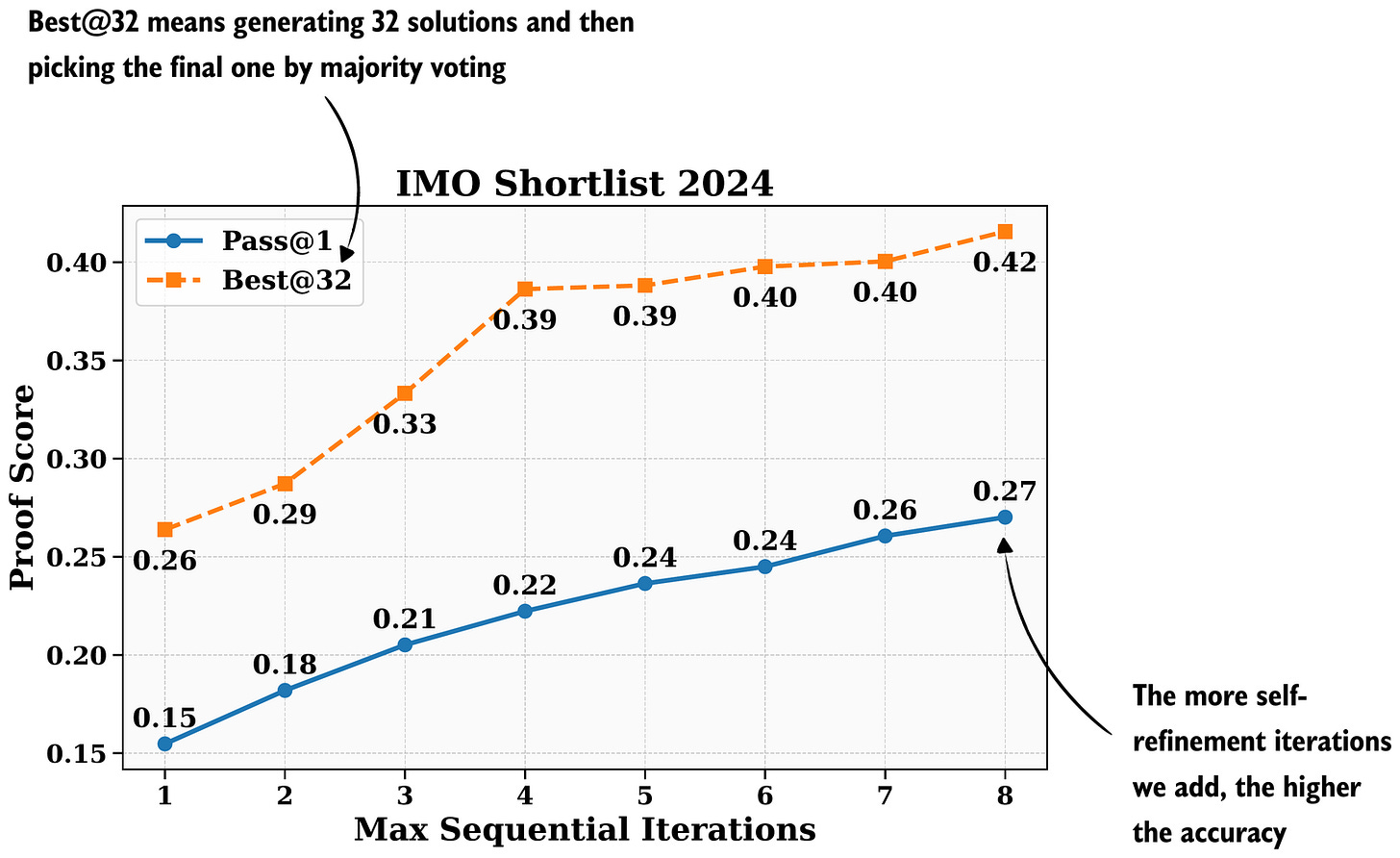

Coming back to the general self-refinement concept shown in Figures 14 and 15, both figures show self-refinement with 2 iterations (the initial one and a refined answer). Of course, we can add more iterations to this process. It’s a classic inference-scaling trade-off: the more iterations we add, the more expensive it becomes to generate the answer, but the higher the overall accuracy.

In the paper, the DeepSeek team used up to 8 iterations, and it looks like the accuracy didn’t saturate yet.

6. DeepSeek V3.2 (Dec 1, 2025)

The reason why we spent so much time on DeepSeekMath V2 in the previous section is that a) it’s a very interesting proof of concept that pushes the idea of Reinforcement Learning with Verifiable Rewards (RLVR) further with self-verification and self-refinement techniques, and b) the self-verification and self-refinement techniques are used in DeepSeek V3.2 as well.

But before we get to this part, let’s start with a general overview of DeepSeek V3.2. This model is a big deal because it performs really well compared to current flagship models.

Similar to several other DeepSeek models, V3.2 comes with a nice technical report, which I will discuss in the next sections.

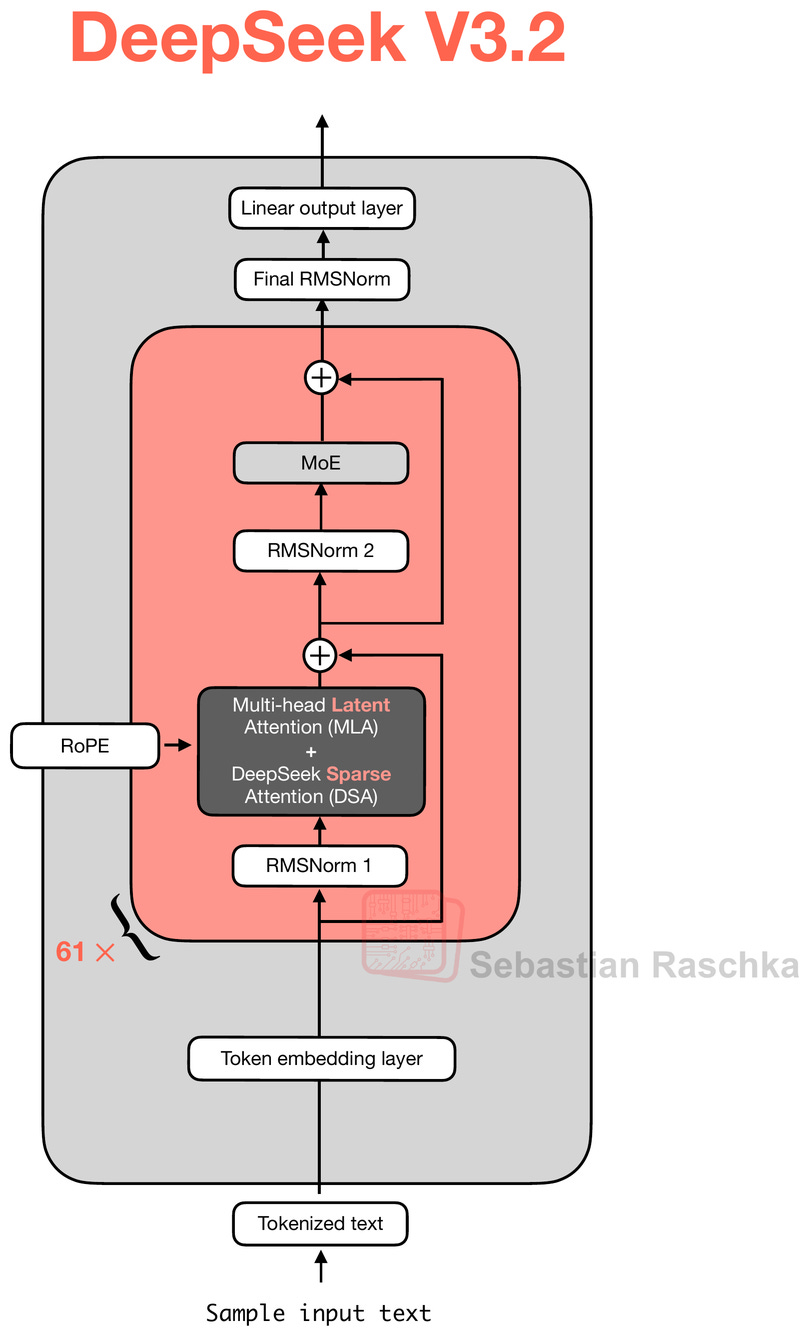

6.1 DeepSeek V3.2 Architecture

The main motivation for this model is, of course, to improve overall model performance. For instance, like DeepSeekMath V2, it achieves gold-level performance on math benchmarks. However, the model is also trained with tool-use in mind and also performs well on other tasks, for instance, code and agentic tasks.

At the same time, the DeepSeek team writes about computational efficiency as a big, motivating factor. That’s why they use the Multi-Head Latent Attention (MLA) mechanism from V2 and V3 together with the DeepSeek Sparse Attention (DSA) mechanism, which they added in V3.2. In fact, the paper says that “DeepSeek-V3.2 uses exactly the same architecture as DeepSeek-V3.2-Exp,” which we discussed in an earlier section.

As I mentioned earlier the DeepSeek V3.2-Exp release was likely intended to get the ecosystem and inference infrastructure ready to host the just-released V3.2 model.

Interestingly, as the screenshot from the paper above shows, the DeepSeek team reverted to using NVIDIA chips (after they allegedly experimented with model training on chips from Huawei).

Since the architecture is the same as that of DeepSeek V3.2-Exp, the interesting details lie in the training methods, which we will discuss in the next sections.

6.2 Reinforcement Learning Updates

Overall, the DeepSeek team adopts the Reinforcement Learning with Verifiable Rewards (RLVR) procedure using the Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO) algorithm similar to DeepSeek R1. However, there are some interesting updates to discuss.

Originally, DeepSeek R1 used

a format reward (to make sure the answer is properly formatted);

a language consistency reward (so that the model doesn’t alternate between different languages when writing its response);

and the main verifier reward (whether the answer, in a math or code problem, is correct or not)

For DeepSeek V3.2, they changed the rewards:

For reasoning and agent tasks, we employ rule-based outcome reward, length penalty, and language consistency reward. For general tasks, we employ a generative reward model where each prompt has its own rubrics for evaluation.

For instance, they removed the format reward but added a length penalty for agentic tasks. Then, for general tasks where there is no symbolic verifier (math) or code interpreter to verify the answer, they use a reward model (another LLM trained to output a reward score).

So, it sounds like the pipeline is no longer purely verifier‑based RLVR like in DeepSeek R1, but a hybrid of RLVR (for verifiable domains) and more standard LLM‑as‑a‑judge reward modeling for everything else.

For the math domain, they state that they additionally “incorporated the dataset and reward method from DeepSeekMath-V2,” which we discussed earlier in this article.

6.3 GRPO Updates

Regarding GRPO itself, the learning algorithm inside the RLVR pipeline, they made a few changes since the original version in the DeepSeek R1 paper, too.

Over the last few months, dozens of papers have proposed modifications to GRPO to improve its stability and efficiency. I wrote about two popular ones, DAPO and Dr. GRPO, earlier this year in my The State of Reinforcement Learning for LLM Reasoning article .

Without getting into the mathematical details of GRPO, in short, DAPO modifies GRPO with asymmetric clipping, dynamic sampling, token-level loss, and explicit length-based reward shaping. Dr. GRPO changes the GRPO objective itself to remove the length and std normalizations.

The recent Olmo 3 paper also adopted similar changes, which I am quoting below:

Zero Gradient Signal Filtering: We remove groups of instances whose rewards are all identical (that is, a batch with zero standard deviation in their advantage) to avoid training on samples that provide zero gradient, similar to DAPO (Yu et al., 2025). [DAPO]

Active Sampling: We maintain a consistent batch size in spite of zero gradient filtering with a novel, more efficient version of dynamic sampling (Yu et al., 2025). See OlmoRL Infra for details. [DAPO]

Token-level loss: We use a token-level loss to normalize the loss by the total number of tokens across the batch (Yu et al., 2025), rather than per-sample to avoid a length bias. [DAPO]

No KL Loss: We remove the KL loss as a common practice (GLM-4.5 Team et al., 2025; Yu et al., 2025; Liu et al., 2025b) as it allows less restricted policy updates, and removing it does not lead to over-optimization or destabilized training. [DAPO and Dr. GRPO]

Clip Higher: We set the upper-bound clipping term in the loss to a slightly higher value than the lower bound to enable larger updates on tokens, as proposed by Yu et al. (2025). [DAPO]

Truncated Importance Sampling: To adjust for differences between log probabilities from the inference and training engines, we multiply the loss by the truncated importance sampling ratio, following Yao et al. (2025).

No standard deviation normalization: When calculating advantage, we do not normalize by the standard deviation of the group, following Liu et al. (2025b). This removes a difficulty bias, where questions with low standard deviation in their rewards (for example, too hard or too easy) have their advantages significantly increased by the normalization term. [Dr. GRPO]

The GRPO modifications in DeepSeek V3.2 are a bit less aggressive, which I summarized in a similar style as Olmo 3 did:

Domain‑specific KL strengths (including zero for math): Instead of always dropping KL like DAPO and Dr. GRPO do for math‑style RL, DeepSeek V3.2 keeps a KL term in the objective but tunes its weight per domain. However, they also note that very weak or even zero KL often works best for mathematics. (But instead of removing it completely, it becomes a hyperparameter.)

Unbiased KL estimate: As mentioned above, DeepSeek V3.2 doesn’t remove the KL penalty. And in addition to treating it as a tuning knob, they propose a fix to how the KL penalty is estimated in GRPO by reweighting the KL term with the same importance ratio used for the main loss, so the KL gradient actually matches the fact that samples come from the old policy rather than the current one.

Off‑policy sequence masking: When they reuse rollout data (rollout is simply jargon for the full sequence the model generates) across many gradient steps, DeepSeek V3.2 measures how far the current policy has drifted from the rollout policy on each full answer and simply drops those sequences that both have negative advantage and are “too off‑policy”. So, this prevents the model from learning from overly off‑policy or stale data.

Keep routing for MoE models: For the Mixture‑of‑Experts backbone, they log which experts were activated during rollout and force the same routing pattern during training, so gradient updates are for those experts that produced the sampled answers.

Keep sampling mask for top‑p / top‑k: When rollouts use top‑p or top‑k sampling, DeepSeek V3.2 stores the selection mask and reapplies it when computing the GRPO loss and KL, so the action space at training time matches what was actually available during sampling.

Keep original GRPO advantage normalization: Dr. GRPO shows that GRPO’s length and per‑group standard‑deviation normalization terms bias optimization toward overly long incorrect answers and over‑weight very easy or very hard questions. Dr. GRPO fixes this by removing both terms and going back to an unbiased PPO‑style objective. In contrast, DAPO moves to a token‑level loss that also changes how long vs short answers are weighted. DeepSeek V3.2, however, keeps the original GRPO normalization and instead focuses on other fixes, such as those above.

So, overall, DeepSeek V3.2 is closer to the original GRPO algorithms than some other recent models but adds some logical tweaks.

6.4 DeepSeek V3.2-Speciale and Extended Thinking

DeepSeek V3.2 also comes in an extreme, extended-thinking variant called DeepSeek V3.2-Speciale, which was trained only on reasoning data during the RL stage (more akin to DeepSeek R1). Besides training only on reasoning data, they also reduced the length penalty during RL, allowing the model to output longer responses.

Generating longer responses is a form of inference scaling, where responses become more expensive due to the increased length, in return for better results.

7. Conclusion

In this article, I didn’t cover all the nitty-gritty details of the DeepSeek V3.2 training approach, but I hope the comparison with previous DeepSeek models helps clarify the main points and innovations.

In short, the interesting takeaways are:

DeepSeek V3.2 uses a similar architecture to all its predecessors since DeepSeek V3;

The main architecture tweak is that they added the sparse attention mechanism from DeepSeek V3.2-Exp to improve efficiency;

To improve math performance, they adopted the self-verification approach from DeepSeekMath V2;

There are several improvements to the training pipeline, for example, GRPO stability updates (note the paper goes into several other aspects around distillation, long-context training, integration of tool-use similar to gpt-oss, which we did not cover in this article).

Irrespective of the relative market share of DeepSeek models compared to other smaller open-weight models or proprietary models like GPT-5.1 or Gemini 3.0 Pro, one thing is for sure: DeepSeek releases are always interesting, and there’s always a lot to learn from the technical reports that come with the open-weight model checkpoints.

I hope you found this overview useful!

8. DeepSeek’s mHC: Manifold-Constrained Hyper-Connections

Efficiency and performance tweaks in the transformer architecture usually focus(ed) on the normalization, attention, and FFN modules.

For instance:

Normalization: LayerNorm → RMSNorm → Dynamic TanH

Attention: Grouped-query attention, sliding window, multi-head latent attention, sparse attention

FFN: GeLU → SiLU, SiLU → SwiGLU, Mixture of Experts.

On December 31st, 2025 DeepSeek shared new interesting research on improving the residual path: mHC: Manifold-Constrained Hyper-Connections.

In short, it’s built on the hyper-connections (HC) approach, which generalizes the regular (identity) residual connection into a learned one by widening the residual stream via multiple parallel ones and allowing information to mix across those parallel layers.

They then take the HC idea a step further and propose mHC, which constrains the residual mixing to lie on a structured, norm-preserving manifold. They found that this "m"-modification improves training stability.

This adds a small amount of overhead, but they get much better training stability and convergence.

This magazine is a personal passion project, and your support helps keep it alive.

If you’d like to support my work, please consider my Build a Large Language Model (From Scratch) book or its follow-up, Build a Reasoning Model (From Scratch). (I’m confident you’ll get a lot out of these; they explain how LLMs work in depth you won’t find elsewhere.)

Thanks for reading, and for helping support independent research!

If you read the book and have a few minutes to spare, I’d really appreciate a brief review. It helps us authors a lot!

Your support means a great deal! Thank you!

Love these details, thanks for the write up

amazing work!